A swap is an exchange of one asset (or liability) for another in order to change some of the characteristics of the asset being held by an investor. Usually the objective of the investor is to change only a few, even only one, of the characteristics of the asset. In an interest rate swap, an investor may exchange, or swap, a floating-rate bond for a fixed-rate bond. The bonds being exchanged will be very close in terms of the amounts involved, credit risk, and maturity but may be different only in that the interest rate on one bond may be fixed for the life of the bond while the interest rate on the other may change according to a prearranged formula over the life of the bond. Since the investor who wishes to make such an exchange may find it very difficult to find another investor who wants to make the opposite transaction, that is, be the counterparty to the swap deal, financial institutions usually have to get involved to facilitate the swap transactions.

There are two main reasons for investors to enter into swap deals. The most important reason is that swaps allow some market imperfections to be exploited. In other situations, needs of an investor may change after the initial investment has been made and the investor may wish to hold an asset (or liability) with slightly different characteristics. A swap allows such a change at a lower cost than the alternative of liquidating the original asset that is no longer desired and acquiring a new one.

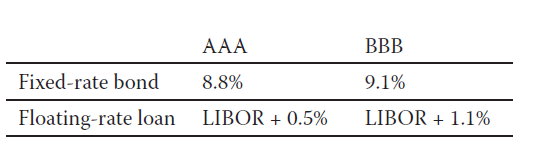

Mechanics of an interest rate swap motivated by a desire to exploit a market imperfection are best explained with the help of an example. Let us say that firm AAA plans to borrow $100 million for five years at a fixed rate of interest. At the same time, firm BBB is planning to raise the same amount of funds in the form of a five-year floating-rate loan. Both firms inquire about the rates they will have to pay in the two segments of the financial markets—the fixed-rate market and the floating-rate market—and obtain the following quotes:

Table 1

If each firm were to raise the type of funds it needs, the total annual cost for the two firms would be 8.8 percent (the rate firm AAA would have to pay) plus LIBOR + 1.1 percent (BBB’s annual cost for the loan). This total cost adds up to (LIBOR + 9.9) percent. Suppose, however, that the two firms raise the opposite type of funds from what they need. AAA raises floating-rate funds and BBB raises fixed-rate funds. They then “swap” their funds. They agree that AAA will pay BBB the cost of fixed-rate funds and BBB will become responsible to AAA for the cost of floating-rate funds. The total cost in this case would be {9.1 + (LIBOR + 0.5)} or (LIBOR + 9.6) percent—a saving of 0.3 percent per annum between the two firms. A financial institution that would have observed this anomaly would bring the two firms together, convince them to raise the type of funds they do not need and swap their obligations. The savings of 0.3 percent will be divided between the three parties—the two firms and the financial institution. The financial institution will bear the risk that each party fulfills its obligations.

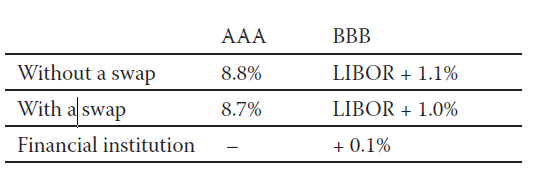

After the swap, the two firms and the financial institution will have the following obligations and cash flows. Firm AAA would have raised the loan at LIBOR + 0.5 percent and hence will have to pay the lender this amount every year. It will also have to pay firm BBB 9.1 percent annually for the fixed-rate bond that firm BBB would have raised on its behalf. In exchange, it will receive, say, LIBOR + 1.0 percent from BBB for the loan. Firm AAA’s net cash flow will end up being {–(LIBOR + 0.5) – 9.1 + (LIBOR + 1)} or a new outflow of 8.6 percent per annum.

Firm BBB would pay the bond holder 9.1 percent— amount that it would receive from firm AAA—and will have to pay AAA (LIBOR + 1) percent for the loan. Its new cash flow will end up being (LIBOR +1) percent. In addition, we can assume that firm AAA will pay 0.1 percent to the financial institution for its help in the intermediation process.

The cash flows of the three parties with and without the swap can be compared easily.

Table 2

The market imperfection that the parties exploited was that the floating-rate and fixed-rate markets assessed different risk premiums for the two firms. Assuming that the expected value of LIBOR over the life of the contract was 8.3 percent, AAA was assessed the same risk by the two market segments whereas the floating-rate market considered BBB to be riskier than the fixed-rate market.

The Bank for International Settlements estimates that the notional amount of interest rate swaps outstanding in the over-the-counter market at the end of December 2007 was $393 trillion. The largest share of this market was for interest rate swaps in euros ($146 trillion) followed by dollars ($130 trillion) and yen ($53 trillion).

Bibliography:

- Paul D. Cretien, “Smoother Way to Trade Interest Rate Swaps,” Futures (v.37/1, 2008);

- Frank Fabozzi and Franco Modigliani, Capital Markets: Institutions and Instruments (Pearson Prentice Hall, 2009);

- John Hull, Options, Futures and Other Derivatives (Pearson/ Prentice Hall, 2009);

- Ira G. Kawaller, “Interest Rate Swaps: Accounting Economics,” Financial Analysts Journal (v.63/2, 2007);

- Patel, “Interest Rate Swaps: Under Pressure,” Risk (v.20/3, 2007).

This example Interest Rate Swaps Essay is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need a custom essay or research paper on this topic please use our writing services. EssayEmpire.com offers reliable custom essay writing services that can help you to receive high grades and impress your professors with the quality of each essay or research paper you hand in.