Gerrymandering is the practice of drawing political boundaries—especially the boundaries of legislative districts—in such a way as to obtain political advantage. The term derives from the claim of critics that a legislative district drawn by supporters of Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry in 1812 was shaped like a salamander, or “Gerry-mander.”

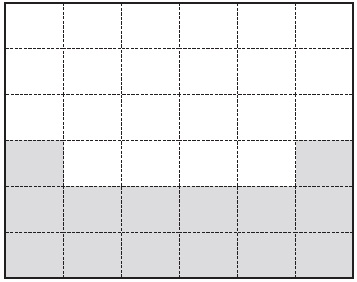

Consider the hypothetical region shown in Figure 1, with supporters of party A indicated by the light squares and supporters of party B by the dark squares. In proportional voting systems, the fact that 22/36 of the voters support party A would mean that party A would get that proportion—22/36—of the representation. But in a winner-take-all voting system (as in the United States), the region must be divided into a fixed number of single-winner districts. Assume that by virtue of its population, the region is entitled to three legislators, and hence the region must be divided into three legislative districts.

Figure 1 Region With Supporters of Party A (Light Squares) and Party B (Dark Squares)

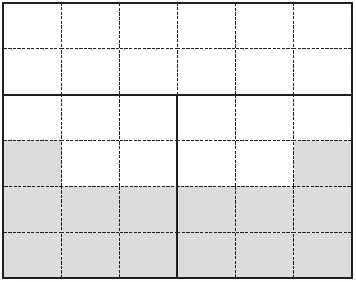

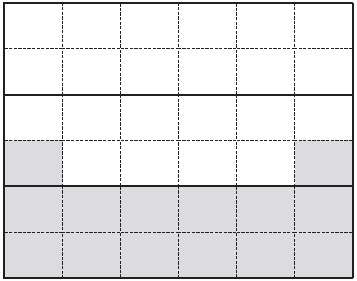

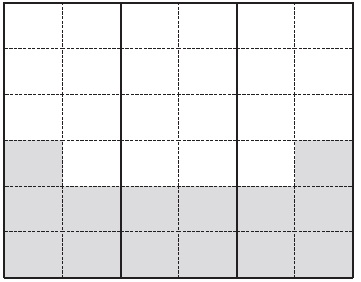

If the district lines are drawn as in Figure 2, then party B will win two out of the three districts (because it has a majority of the votes in each of the two lower districts, while party A has all the votes in the upper district). On the other hand, if the district lines are drawn as in Figure 3, then party A will win two out of the three districts (the top two districts). And if they are drawn as in Figure 4, then party A will carry all three districts. Thus, whoever gets to draw the lines can maximize partisan advantage.

Figure 2 Party B Wins Two out of Three Districts

Figure 3 Party A Wins Two out of Three Districts

Figure 4 Party AWins All Three Districts

Different district lines yield different political outcomes because, under winner-take-all voting, a party wins a district whether it has a large majority (with many wasted votes) or a narrow majority. So by arranging for one’s own party to win its districts as narrowly as possible and for one’s opponents to win their districts with as many wasted votes as possible, one can maximize the number of districts won. (Of course, a party might not want to make its winning edge too narrow, lest a shift in voter sentiment lead to an electoral loss.) With modern computer technology and detailed voter databases, it is possible to manipulate political boundaries with great precision.

Several mathematical procedures exist for neutrally drawing district lines—for example, the shortest split-line algorithm. However, it is sometimes thought desirable to have a district made up of people sharing a community of interest (say, living in the same municipality or county, or on the same side of a mountain), factors that cannot readily be accounted for mathematically. Once discretion is allowed, the opportunity exists for manipulation to suit partisan interest.

In Canada and Britain, independent commissions draw the electoral boundaries. In most U.S. states, the state legislatures—which are partisan bodies— draw the congressional district lines. In a few states, a nonpartisan or bipartisan agency—such as Iowa’s Legislative Service Bureau, the Washington State Redistricting Commission, and the Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission—is responsible for drawing the lines. Such agencies are often prohibited from considering any demographic data other than population headcount. In some cases these agencies have the last word; in others the state legislature can amend the commission’s plan within specified limits.

In the United States, after a new census is conducted every 10 years, the states engage in “redisricting,” that is, redrawing their district lines to ensure that each district has roughly equal population. Thus, gerrymandering was once a decennial concern. In 2006, however, the Supreme Court ruled (in League of United Latin American Citizens v. Perry) that there was nothing to prevent a state legislature, when its political control switched from one party to another, from engaging in mid-decade redistricting to change districts drawn earlier in conformity with the census.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that boundary drawing must result in “compact districts of contiguous territory” with roughly equal population. In practice, however, districts have been permitted in all sorts of bizarre shapes. Although the Court barred redrawing district lines so as to obtain excessive partisan advantage, it failed to offer a standard for determining whether a partisan gerrymander is excessive, and it has even allowed patently partisan line drawing to stand. Some Supreme Court justices urge that a standard of excessive partisanship be developed; others believe that no such standard can be constructed.

The Supreme Court has prohibited the drawing of district lines where the intent is to disenfranchise racial or ethnic minorities. Some states created legislative districts where a majority of voters are members of a racial or ethnic minority (so-called majority-minority districts) to ensure that some legislators will be minorities. Republicans often support such “racial gerrymandering,” with the hope that concentrating minority voters (who tend to vote Democratic) will reduce the number of Democratic legislators statewide.

Gerrymandering need not always be done for partisan advantage; sometimes it is used for the bipartisan advantage of incumbents. That is, incumbents of both parties might support a redistricting scheme that makes all incumbents more likely to win reelection. For example, if representatives from party A and party B have been elected from two adjoining districts, each district having voter sentiment divided approximately 50-50 between the two parties, the district lines could be redrawn so that each has a comfortable 70-30 edge, thus assuring reelection.

Bibliography:

- Cox, Gary W. and Jonathan N. Katz. 2002. Elbridge Gerry’s Salamander: The Electoral Consequences of the Reapportionment Revolution. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Forgette, Richard and Glenn Platt. 2005. “Redistricting Principles and Incumbency Protection in the U.S. Congress.” Political Geography 24(8):934-51.

This example Gerrymandering Essay is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need a custom essay or research paper on this topic please use our writing services. EssayEmpire.com offers reliable custom essay writing services that can help you to receive high grades and impress your professors with the quality of each essay or research paper you hand in.