Twenty-five years into the global HIV/AIDS epidemic, HIV infection rates remain alarmingly high, with more than 4 million new infections every year. Despite the rapid global spread of HIV, most people in both industrialized and developing countries are at relatively low risk of HIV infection. Comprehensive prevention programs directed at all segments of the general population can help to improve awareness, change social norms, reduce stigma and discrimination, promote less risky behavior, and reduce new infections. However, careful analysis of the sources of new infections in subpopulations is essential in order to focus relevant interventions and maximize their impact. A combination of risk avoidance (abstinence, mutual fidelity) and risk reduction (reduction in the number of sexual partners, treatment of sexually transmitted diseases, correct and consistent condom use, male circumcision, and needle exchange) have proven to be successful all over the globe.

Effective targeted prevention interventions can also lower the number of patients requiring costly drug treatments and boost the sustainability of expensive antiretroviral therapy (ART). At the same time, successful ART makes prevention more acceptable and helps in reducing stigma and discrimination.

To control HIV infections, the focus should be on the populations experiencing the highest rate of infections—often referred to as “high-risk populations,” “most at risk populations,” or “most vulnerable populations” (MVPs). Interventions tailored to specific populations reach a smaller audience than those aimed at the general population, yet they have the possibility to make a disproportionate impact on the course of the epidemic.

MVPs are a relatively smaller segment of the general population that is at higher than average risk of acquiring or transmitting HIV infections. They include discordant couples, sex workers (SWs) and their clients, injection drug users (IDUs) and other drug users, men who have sex with men (MSM), individuals in the armed forces, prisoners, and children of sex workers. A larger group of MVPs, especially in high-prevalence countries, may include HIV-positive pregnant women, sexually active and out-of-school youth, minority populations, migrant and displaced persons, and large populations of women.

There are compelling reasons to reach MVPs:

- They are often marginalized, criminalized, victimized, and discriminated against by law enforcement agencies as well as the general population. As a result they are difficult to reach and have poor access to relevant public health and other services.

- Segmentation of the various subpopulations allows for more specific, appropriate, and effective interventions.

- There are numerous proven interventions that can control the epidemic in IDUs, SWs, and MSM.

Risk and Vulnerability

An individual’s risk of acquiring or transmitting HIV is affected by a variety of factors, such as sexual behavior, drug use, male circumcision, and leaving sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) untreated. High-risk individuals engage in behaviors that expose themselves to the risk of HIV infection, such as unprotected casual sex with multiple partners, sharing needles, and commercial sex.

Risk can be further compounded when the HIV-positive individual is suffering from acute HIV infection. Acute infection refers to the period of time immediately after a person is infected with HIV. Characterizing this phase is prolific viral replication and an acute drop in the CD4 count. Persons with acute HIV infection are extremely infectious, as the potential for an individual to transmit the virus increases eight- to tenfold.

In addition to individual risk behaviors, some vulnerable populations face greater susceptibility to HIV/AIDS. Societal factors, often beyond the control of the individual, may also increase the risk of infection. These include poverty, unemployment, illiteracy, gender inequities and gender-based violence, cultural practices, human rights abuses, and lack of access to information and services.

Women face increased vulnerability to infection due to biological, social, and economic factors. They often lack the power to negotiate safer sex with their partners. Because of economic inequalities, some women enter sex work or perform transactional sex for economic survival. Furthermore, women are more vulnerable to infection than men because of biology: The female genital tract has more exposed surface area than the male genital tract, semen has a greater HIV concentration than vaginal fluids, and a larger amount of semen is exchanged during intercourse than vaginal fluids.

Orphans and children of MVPs are also particularly vulnerable. Whether the parent is a SW or IDU, HIV-positive or HIV-negative, living or deceased, these children need special attention. MVPs with children may not be coherent enough to support a child emotionally or financially. They may not be physically present, may be ill due to HIV, or may have died. Many times, children of HIV-positive parents serve as caretakers.

Understanding the Local Dynamics of the Epidemic

The population of MVPs differs by the type and level of epidemic. Through investigation of the incidence, distribution, and causes of HIV in a society, epidemiologists can predict which populations are most vulnerable to, and at risk of, HIV infection.

In lower-prevalence countries, containing the epidemic in MVPs can have a wide-reaching effect on how the general population experiences HIV and AIDS. Accurate epidemiological and behavioral data can pinpoint which populations are at high risk and, therefore, which targeted interventions should be implemented to address those populations. By targeting MVPs, the progression from low HIV prevalence to higher HIV prevalence in the general population may be prevented.

In higher-prevalence countries, with an increased pool of infected individuals, a more effective strategy would be to identify those infected through targeted counseling and testing and other community-based interventions. In this environment, programs should focus on discordant couples and other at-risk populations such as sexually active youth, young adults, and women and provide both risk avoidance and risk reduction programs.

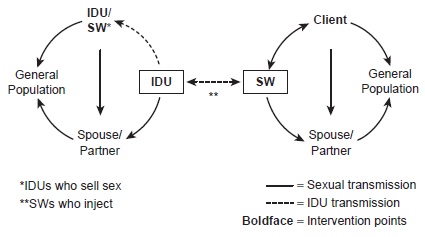

In many contexts, the relationship between sex work and injection drug use is quite close (Figure 1), and prostitution and injection drug use have been the engines that have fueled the epidemic. Many SWs use injection drugs and many drug users resort to sex work to pay for their injection drug use. These IDU/SWs not only risk transmitting HIV through the sharing of injection drug paraphernalia but also can pass the infection sexually. HIV infections will then reach bridge populations and allow the virus to infect the general population.

Figure 1 HIV Transmission Through Sex Work and Injection Drug Use

Overall, targeted interventions may take various forms, depending on the social, cultural, economic, political, and legal specifics of the high-risk group. The discussion that follows focuses on some most at risk populations and appropriate interventions.

Sex Workers

SWs are a diverse and sizable population. They can be male, female, or transgender and work in a variety of environments, including brothels, bars, or on the streets. In some societies, such as in Amsterdam, Senegal, and Nevada, sex work is legal or decriminalized. These legal SWs have access to health and social services. In some societies, sex work is likely to be a personal choice. In many others it may be due to poverty or a lack of education and employment opportunities, or it may be fueled by trafficking of girls and women. Sex work is also often used as a survival tactic during severe societal disruption caused by civil wars or natural disasters when no services are available and necessities are scarce.

In many countries, sex work is a driving factor fueling the HIV epidemic. Sustained and meaningful interventions are complicated by a variety of factors, including a lucrative commercial sex industry, low condom use, high levels of STDs, a hard-to-reach, highly mobile population of SWs and clients, and the absence of an atmosphere that encourages access to prevention programs. Awareness and understanding of a particular community’s environment is essential in tailoring a relevant, effective message. The focus should be on harm reduction and increased knowledge among SWs as well as parallel interventions for clients and partners of SWs. Interventions should include the promotion of condom knowledge, access, and use as well as improved health care, including antiretroviral therapy, STD screening, checkups, and treatment. Other critical areas for targeting and scaling up interventions include building the capacity of community organizations; facilitating policy change to reduce discrimination and stigmatization; creating an enabling environment; harmonizing interventions with other HIV/STD, reproductive health, and drug prevention programs; and providing ongoing technical support and effective management and monitoring.

Men who Have Sex with Men

As with interventions targeting SWs, interventions targeting MSM are essential, as well as challenging. This population is largely neglected in most countries and in urgent need of targeted, relevant HIV interventions. Because MSM often have sex with women, they possess the potential to spread HIV to the general population.

Reaching the MSM population is a difficult task for several reasons. First, this group faces a high level of stigma and discrimination by medical service providers and the general population. In many countries, homosexuality is illegal, and fear of legal repercussions drives the population further underground. Also, MSM do not often self-identify as “homosexual.” Cultural perceptions of what constitutes homosexuality can vary widely, and men adopt different definitions based on these perceptions. Lastly, the MSM population is extremely diverse in nature. MSM may include monogamous homosexuals, male bisexuals, transgender individuals, heterosexual SWs, homosexual SWs, and MSM who are IDUs.

Injection Drug Users

IDUs are another key risk population for contracting and transmitting HIV. There are approximately 13 million IDUs worldwide, and the number is rising. Many lack adequate resources or access to sterile needles and syringes, especially in developing countries. They are treated as criminals in many societies and denied access to basic services and support. IDUs face considerable legal obstacles, such as laws prohibiting the possession of drug paraphernalia and drugs, and laws against aiding and abetting. An additional complication is that drug use is often accompanied by sex work.

Though sex is the chief mode of transmission in the spread of HIV, at least 10 percent of new infections globally are those contracted through injection drug use. In some countries, especially those with a low prevalence of HIV such as China and the countries of Eastern Europe, IDUs are at the center of the epidemic. Historically a problem of rich countries, HIV transmission through IDUs is now observed throughout the world.

Considering this growing trend of injection drug use, new and scaled-up interventions are imperative to prevent the spread of HIV within and from IDUs. In low-prevalence countries, interventions targeting IDUs can limit transmission to SWs and therefore prevent a generalized epidemic. In countries already battling a high-prevalence epidemic, IDU interventions are critical to prevent an increase in incidence.

Harm reduction interventions should include ART, drug substitution therapy, needle exchange and distribution, condom and bleach distribution, outreach, peer education programs, and social network interventions. Though needle distribution programs are recognized as a cost-effective way to reduce HIV transmission, they remain controversial in many countries, including the United States. Opponents of needle exchange or distribution view the practice as “enabling” and encouraging drug use. As an alternative, bleach distribution programs have been implemented in countries with laws prohibiting or restricting needle distribution.

Individuals in the Armed Services

The armed forces, police, and other uniformed services around the world face a serious risk of HIV and other STDs, with infection rates significantly higher than the general population. Members of uniformed services can serve as a core transmission group for these infections to the general population. The nature of their work often requires that they be posted or travel away from home for extended periods of time, or they must await proper housing before sending for their families. Confronting risk daily inspires other risky behaviors, and a sense of invincibility may carry over into personal behavior. These groups tend to have more frequent contact with SWs, which increases the likelihood of passing on HIV and STDs to other partners, including their wives or girlfriends. The frequent and excessive use of alcohol and other behavior-modifying drugs plays a major role in risky sexual behavior.

Other High-Risk Populations

Other vulnerable populations include prisoners, migrants, refugees and internally displaced persons, truck drivers, transgender individuals, and out-of-school youth. To prevent transmission within these groups and to the general population, early targeted interventions should be implemented.

HIV/AIDS care and treatment are essential; however, prevention interventions are equally crucial. If large-scale and effective HIV prevention interventions are properly supported, the cost and need for treatment decreases.

Lower-level prevalence areas offer public health professionals an opportunity to act swiftly and avoid further expansion of the epidemic. Even in higher-prevalence countries, targeting the most at-risk individuals is important to prevent the further spread of the epidemic in the general population. National HIV prevention efforts need to be prioritized, directed, and scaled up to the populations most vulnerable and at risk of infection.

Many factors improve the ability for targeted interventions to succeed. Laws and policies directly challenging stigma and discrimination against people who have HIV, or are perceived to be at a risk for HIV, are essential. Interventions must also address contextual issues and be sensitive to local cultural and social perceptions surrounding HIV/AIDS. New technologies such as microbicides, male circumcision, and preexposure prophylaxis may become extremely valuable tools in preventing HIV among the most vulnerable populations.

All in all, HIV interventions must focus on the populations most vulnerable to HIV, irrespective of the level of the epidemic. This basic tenet of public health continues to be a cost-effective approach to controlling HIV.

Bibliography:

- Ball, Andrew L., Sujata Rana, and Karl L. Dehne. 1998. “HIV Prevention among Injecting Drug Users: Responses in Developing and Transitional Countries.” Public Health Reports 113:170-81.

- Barnett, Tony and Justin Parkhurst. 2005. “HIV/AIDS: Sex, Abstinence, and Behavior Change.” Lancet: Infectious Diseases 5:590-93. Burris, Scott. 2006. “Stigma and the Law.” Lancet 367:529-31.

- Chatterjee, Patralekha. 2006. “AIDS in India: Police Powers and Public Health.” Lancet 367:805-6.

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). 2006. “Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic.” Retrieved March 24, 2017 (http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2006/2006_gr_en.pdf).

- Lamptey, Peter L. and David Wilson. 2005. “Scaling Up AIDS Treatment: What Is the Potential Impact and What Are the Risks?” PLoSMedicine 2(2):e39.

- Monitoring the AIDS Pandemic (MAP) Network. 2005. “MAP Report 2005: Drug Injection and HIV/AIDS in Asia.” Retrieved March 24, 2017 (http://apps.searo.who.int/PDS_DOCS/B1485.pdf).

- Monitoring the AIDS Pandemic (MAP) Network. 2005. “MAP Report 2005: Male to Male Sex and HIV/AIDS in Asia.” Retrieved March 24, 2017 (http://siteresources.worldbank.org/SOUTHASIAEXT/Resources/223546-1192413140459/4281804-1231540815570/5730961-1236714389204/MAPMBook04July05.pdf).

- Parker, Richard, Peter Aggleton, Kathy Attawell, Julie Pulerwitz, and Lisanne Brown. 2002. HIV-Related Stigma and Discrimination: A Conceptual Framework and an Agenda for Action. Horizons Report. Washington, DC: Population Council.

- Rekart, Michael. 2005. “Sex-Work Harm Reduction.” Lancet 366:2123-34.

- Roura, Maria. 2005. “HIV/AIDS Interventions in Low Prevalence Countries: A Case Study of Albania.” International Social Science Journal 57(186):639-48.

This example HIV/AIDS Essay is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need a custom essay or research paper on this topic please use our writing services. EssayEmpire.com offers reliable custom essay writing services that can help you to receive high grades and impress your professors with the quality of each essay or research paper you hand in.