There is a great deal of confusion in the use of the terms homicide and murder, partly because criminologists and lawyers tend not to use the terms in the same way. Legally, homicide is the killing of one person by another, and homicide is divided into justifiable and criminal homicides. A justifiable homicide is the killing of another in self-defense when faced with the danger of serious bodily injury. This includes killing of combatants during war, legal executions, and homicides by police in the course of carrying out their duties. A civilian justifiable homicide is the killing of another when faced with death or to prevent the death of another.

Criminal homicides consist of murder and manslaughter. The Model Penal Code, used by many states, defines criminal homicide as the act of purposely, knowingly, recklessly, or negligently causing the death of another human being. Murder is defined as the killing of another human being with malice aforethought, while manslaughter is killing without malice aforethought. The term malice aforethought is applied to murders that resulted from the intentional infliction of serious bodily harm, from outrageously reckless conduct, or, in some states, from a felony such as robbery. Manslaughter is defined as murder committed in the heat of passion or the responsibility for another’s death through reckless conduct, such as driving a car with defective brakes in a large city.

Most of the research on criminal homicides focuses on murders, and criminologists tend to use the term homicide to include murder. As a rule, their research on homicide does not include justifiable homicides or negligent manslaughters. Criminologists tend to use the terms homicide, criminal homicide, and murder interchangeably.

Data

According to nationwide Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) statistics for 2004, there were 16,137 murders and non-negligent manslaughters in the United States, a rate of 5.5 per 100,000 inhabitants. Criminal homicide is a male crime. According to 2004 data, 77.8% of homicide victims and 64.4% of offenders were males. Females were more frequently victims (21.9%) than offenders (7.1%), a fact reflected in their higher level of victimization in intimate partner murders.

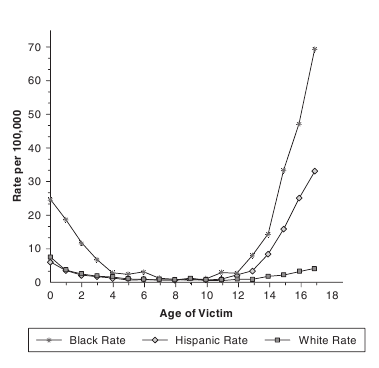

With respect to race, the murder victimization rate for Blacks was 18.2 per 100,000, which is more than five times higher than the rate for Whites (3.2 per 100,000). The Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program does request information from police departments on whether murder victims and offenders are of Hispanic origin; however, there is typically a large amount of information missing from the reports regarding this variable. California, though, is the largest state and does report homicide rates for Hispanics. For 2004, the homicide rate for Hispanics in California was intermediate (8.1 per 100,000), that is, between the rates for Whites (2.6) and for Blacks (31.6).

The highest homicide victimization rates are for those 18 to 24 years old. The rate for that age group was 14.3 per 100,000. The next highest rate is for victims ages 25 to 34, which was 11.1 per 100,000. The rates for the remaining age groups were less than 5 per 100,000.

With respect to the relationship between victim and offender prior to the offense, the largest proportion (25.9%) were simply classified by police and the FBI as homicides in which the “offender was known to the victim.” A little less than 1 in 10 murders (9.4%) involved intimate partner relationships; other family relationships were involved in 7.6% of murders.

Strangers accounted for 12.9% of murder victims, but there was no victim–offender relationship information on 44.1% of the murders.

Not surprisingly, over half (51%) of the murders in 2004 were committed with handguns. If the 14% attributed to other types of firearms is included, 65% of murders involved the use of firearms of one type or another. The remaining 34% involved other types of weapons such as knives, blunt objects, hands, or feet. The three most frequent motives for homicide were brawls and arguments (30.5%), followed by robbery (7.0%) and drug-related motives (3.9%).

One recent development has been the decline in homicide rates, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Homicide Rates in the United States: 1960–2004

Beginning in 1991, there was a downturn in homicide rates, which continued through 2004. In 1991, the homicide rate was 9.8 per 100,000 population; by 2004, the homicide rate was 5.3 per 100,000, a 34.8% decrease. Among the explanations offered for the decline in homicides are the following:

- The growth of homicide during the 1980s was largely due to the increase in the 15-to-24 age group. The decline beginning about 1992 was partly accounted for by a decline in the 15-to-24 age group.

- Beginning about 1993, there has been a decline in handgun homicide among both Whites and Latinos, but the greatest decline has been among Black youth.

- Drug markets may have matured and stabilized, and other dispute resolution mechanisms may have emerged.

- Economic expansion has increased the number of legitimate job opportunities and increased the amount of interaction between legal and illegal opportunities to earn money.

Arrest Clearances

It is obvious that in the event of any crime, including homicide, an offender should be arrested. The FBI’s crime reporting program specifies that a law enforcement agency has cleared a particular offense when at least one person is arrested, charged with the commission of an offense, and turned over to the court for prosecution. Arrest clearances are extremely important to individual officers and law enforcement agencies as measures of performance and to the public for several reasons:

- Regardless of the goals of criminal justice, the process begins with the arrest of offenders. Without arrests, there is neither further processing of offenders nor reduction of crime.

- If offenders are not arrested they are free to offend again, which increases the risk of victimization.

- Failure to arrest offenders further traumatizes victims’ families and contributes to an increase in the fear of violent victimization.

- Because clearances are a performance measure, failure to arrest undermines the morale of law enforcement personnel and agencies.

- When there are no arrests, there is no information on offenders, which limits research on offenders because of incomplete or biased data.

The problem is that for violent crimes in general, and homicide in particular, arrest clearances have been falling since at least 1960, as Figure 2 indicates. Arrest clearances are reported annually as the percentage of crimes for which one or more persons have been arrested. The percentage of homicides cleared by arrest in 1960 was 92.3%. Figure 2 shows that it declined almost linearly from year to year through 2004, when arrest clearances for homicide were 62.6%. Put another way, of the 16,137 homicides in 2004, no one was arrested for 37.4%, or 6,035 events.

Interest in arrest clearances has increased, but the available body of research distinguishes cleared homicides from uncleared homicides on only a few characteristics. In other words, for characteristics such as gender and race/ethnicity, some studies show differences between cleared and uncleared homicides and other studies do not.

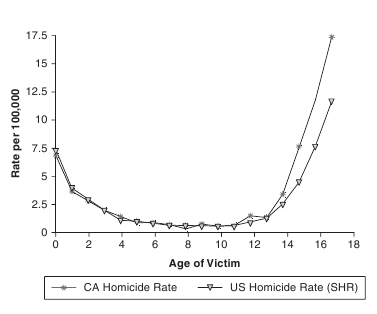

However, there is agreement that homicides involving very young victims are more likely to be cleared than homicides involving older victims. The higher clearance rate for murders of small children is probably a consequence of low homicide rates and very high surveillance. A number of authors have noted that the rate of homicide of children between about 6 and 12 years of age is extremely low. This age group is also under more surveillance by agents such as parents and schools than are other age groups.

Homicides involving weapons other than firearms are more frequently cleared by arrest. The reason for this is that firearms provide the opportunity for individuals to kill at a greater distance and minimize the amount of evidence left at the scene.

Drug-related homicides are less likely than non-drug related homicides to be cleared by arrest. While many of these offenses involve business-related conflicts, they also raise the possibility that third parties refuse to cooperate with the police for fear of being targeted.

Figure 2. Arrest Clearances for Homicide: 1960–2004

Finally, the research is consistent in showing that nonstranger homicides (those committed by family, friends, acquaintances) are cleared more frequently than stranger homicides. One of the most easily cleared offenses involves intimate partners. For example, a physically abused wife decides she will no longer be beaten and kills her husband. When she realizes what she has done, she calls the police, awaits their arrival, and freely confesses.

Law enforcement has begun to come to terms with the declining clearance rates for homicide by an increasing use of cold case squads. There are two reasons that cold case squads are useful in clearing homicides. First, homicides have no statute of limitations and, second, conventional wisdom holds that homicides that have not developed significant leads or witness participation within 72 hours after the event are unlikely to be cleared. The statute of limitations for a crime refers to the time period following the crime during which an offender can be prosecuted. Unless there are some special legal provisions, most crimes cannot be prosecuted after a certain statutory time has passed. Homicide has no statute of limitations.

While cold case squads vary in size and organization throughout the United States, one of their major values is that they have access to technology, investigative methods, and resources not available one or two decades ago. DNA analysis is probably the best known. However, there have been advances in fingerprint technology that include systems for lifting prints from leather and cloth as well as systems that use lasers.

Bibliography:

- Blumstein, A., & Wallman, J. (Eds.). (2000). The crime drop in America. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Riedel, M., & Jarvis, J. (1998). The decline of arrest clearances for criminal homicide: Causes, correlates, and third parties. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 9, 279–305.

- Riedel, M., & Welsh, W. N. (in press). Criminal violence: Patterns, causes, and prevention (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: Roxbury.

- Turner, R., & Kosa, R. (2003). Cold case squads: Leaving no stone unturned. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Assistance.

- Wellford, C., & Cronin, J. (1999). An analysis of variables affecting the clearance of homicides: A multi-state study. Washington, DC: Justice Research and Statistics Association.

This example Criminal Homicides Essay is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need a custom essay or research paper on this topic please use our writing services. EssayEmpire.com offers reliable custom essay writing services that can help you to receive high grades and impress your professors with the quality of each essay or research paper you hand in.