Human thoughts, meanings, interpretations, and understandings are basically formulated and negotiated through activity that is influenced by environmental conditions. Understanding and explaining the ways in which environmental conditions influence humans engaged in individual and collective activity within and among institutions is a major problem of educational theoreticians, researchers, and practitioners. A common perception of environment is that humans act on it rather than interact with it. However, active humans and active environments act on each other. Context is a unit of analysis that is often used to account for how environmental conditions shape human activity.

Definition

Context is derived from the Latin contexere, “to join together,” and texere, “to weave.” Context has multiple meanings (e.g., circumstances, settings, activities, situations, and events).

A context is constituted of the interweaving of elements mediating human activity, including material, ideal, and social objects; instrumental tools, such as computers, rulers, and pencils; psychological tools, such as everyday and institutional discourses and cognitive strategies; and rules and regulations, division of labor, participant roles, participation structures, and discourses. The dynamic interrelationship among these elements is a context. At one and the same time, human activity affects context and context affects human activity, co-constructing each other.

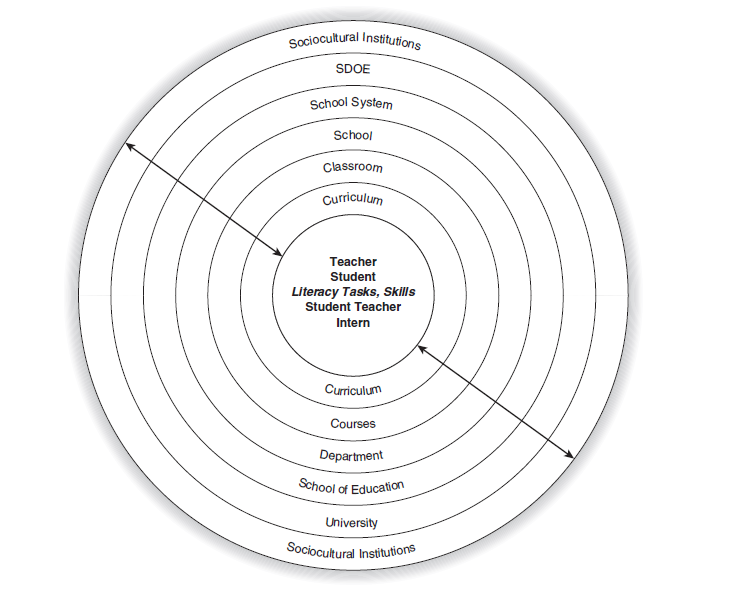

Courtney Cazden represents context as a set of concentric circles in which an activity of interest is located near the center, constituted by and constituting levels of context. Concentric circles reveal the embedded nature of the interactions constituting activities of interest, for example, teacher and pupils engaged in a literacy lesson arranged for the accomplishment of a literacy task lead to the acquisition of a concept or skill; teacher education candidates observing or participating in classroom literacy instruction; teachers participating in a professional development activity; or a professor and students participating in a methods class of a teacher education program.

Education Example

Figure 4 illustrates the idea of using concentric circles to analyze the interplay among levels of context and their potential effects on classroom instruction (top half of the model) and teacher education (bottom half of the model). First, consider the literacy lesson at the core of the concentric circles. The lesson is located in an instructional group, in a classroom. The lesson is structured according to the normative practices of the school in which the classroom is located and the professional practices of the particular classroom teacher. Schools and classroom teachers vary in the way they interpret literacy curriculum and instruction. The literacy curriculum and instruction are regulated by policies of the state department of education, federal mandates, and local boards of education. Curriculum and instruction are organized and guided by the literacy curriculum of the local school system. The selection of and emphasis placed on the particular literacy task pupils are expected to accomplish in the lesson are influenced by statewide tests of achievement and the public posting of grades schools receive based on their performance on the tests. From this perspective, it is easy to understand how the literacy lesson of interest and its qualities are shaped by the interplay between and among a number of interacting contexts. In a sense, the literacy lesson is “caused” by other contexts.

Turning to the bottom half of the model, it is possible to consider the interactive effects of context on the preparation of prospective teachers. Teacher-education accrediting organizations, such as the National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education, and professional associations, such as the International Reading Association, set standards related to teaching in general and to literacy instruction in particular that teacher education programs are expected to meet in order to be professionally accredited. Similarly, the state department of education sets performance standards that teacher education programs must meet for accreditation and standards their students must meet in order to obtain teacher certification. Teacher education candidates participate in learning experiences that are organized by a conceptual framework that specifies the philosophical and theoretical orientation guiding the program and its structure, including subject matter, instruction, and where, and how students will participate in field experiences and student teaching. Similar to classroom instruction, the teacher education is caused by the interaction of layers of context.

Figure 4. Interplay Among Levels of Context

The literacy lesson in the core circle is the nexus where the two complementary contexts merge and co-construct both classroom literacy instruction and the education of prospective teachers. On the one hand, interactions among the layers of one context “author” the literacy lesson before teacher education students arrive to observe or participate in the lesson. On the other, teacher education students bring with them “authoring” effects of interactions among the layers of context of their teacher education program. As the contexts of classroom instruction and teacher education interpenetrate each other, they co-construct a unique learning context for both students and teacher education candidates.

In summary, the interactive effects of the environment and human activity are bidirectional. Context and activity co-construct each other. Context is a useful unit of analysis for analyzing these effects. Contextual analyses can increase the understanding of what facilitates or inhibits teacher and student responses to classroom interventions and how patterns of activity within and among educational institutions affect teacher preparation.

Bibliography:

- Bateson, G. (1972). Steps to an ecology of mind. London: Chandler.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Cazden, C. (1989). Principles from sociology and anthropology: Context, code, Classroom, and culture. In M. C. Reynolds (Ed.), Knowledge base for the beginning teacher (pp. 47–57). New York: Pergamon Press.

- Cole, M., & Griffin, P. (1987). Contextual factors in education: Improving science and mathematics education for minorities and women. Madison: University of Wisconsin, School of Education, Wisconsin Center for Educational Research.

- Erickson, F., & Schultz, J. (1977). When is a context? ICHD Newsletter, 1(2), 5–10.

- Jacob, E. (1997). Context and cognition: Implications for educational innovators and anthropologists. Anthropology and Educational Quarterly, 28, 3–21

- McLaughlin, M. W. (1993). What matters most in teachers workplace context? In M. W. McLaughlin (Ed.), Teachers’ work: Individuals, colleagues, and contexts (pp. 79–103). New York: Teachers College Press.

- Nelson, B. C., & Hammerman, J. J. (1996). Reconceptualizing teaching: Moving toward the creation of intellectual communities of students, teachers, and teacher educators. In M. W. McLaughlin & I. Oberman (Eds.), Teacher learning: New policies, new practices (pp. 3–21). New York: Teachers College Press.

- Talbert, J. E., & McLaughlin, M. W. (1999). Assessing the school environment: Embedded contexts and bottom-up research strategies. In S. L. Friedman & T. D. Wachs (Eds.), Measuring environment across the life span (pp. 197–226). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

This example Context In Education Essay is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need a custom essay or research paper on this topic please use our writing services. EssayEmpire.com offers reliable custom essay writing services that can help you to receive high grades and impress your professors with the quality of each essay or research paper you hand in.