Adult moral agency encompasses several distinct capacities. Moral discernment is recognition of right and wrong. Moral responsiveness is the ability to feel moral emotions such as remorse, empathy, and admiration under appropriate conditions. Moral judgment is the ability to weigh conflicting moral claims and make reasoned choices in specific circumstances. Moral action is putting one’s convictions into practice. Competing theories of moral development differ in how these capacities are conceptualized, the relative weights assigned them, and how they are studied. These differences generate distinctive educational implications.

The theories discussed in this entry represent two major intellectual traditions: the cognitivist tradition, which focuses on mental representation and evaluation, and the behaviorist tradition, which focuses on moral action and external influences on the agent. Although these research programs are different in emphasis, everyone concerned acknowledges that a full account of moral agency must include both action and judgment. For both traditions, the challenge is to address the aspect of moral agency that is not its primary focus.

The Cognitivist Tradition

The cognitivist tradition originates in Jean Piaget’s study of children’s moral reasoning in the mid-1930s. Beginning in the late 1950s, Lawrence Kohlberg extended and elaborated Piaget’s model. Kohlberg’s five-stage developmental theory has spawned a rich research literature, but it has attracted widespread criticism as well, especially for its alleged overemphasis on moral judgment at the expense of action.

Piaget: Moral Development As An Aspect Of Cognitive Growth

In the 1930s, Jean Piaget questioned children about invented rules for marbles. Younger children, he reported, objected that the new rules weren’t part of the game. This moral orientation he characterized as heteronomous: Morality and obligation were imposed from outside. Older children, by contrast, were autonomous in orientation. They did not regard rules as sacrosanct. They considered new ones and evaluated them based on their fairness.

Piaget attributed these differences to two factors. First, interacting with peers and settling disputes without adult aid helps children understand the function of rules and recognize that they are negotiable. Second, older children have developed more complex cognitive structures. Whereas younger children see rules in terms of rewards and sanctions applied to themselves, older children are able to consider effects on other people and consequently can evaluate social arrangements in light of participants’ interests.

Piaget’s work challenged Émile Durkheim’s influential view that moral development is the assimilation of a society’s norms. In contrast to Durkheim’s transmission model, Piaget conceptualized moral development as an active process in which the child begins to question rules and social expectations. This account anticipates constructivist learning theory and is widely reflected in current educational practices—for example, explicit teaching of sharing and turn-taking in preprimary settings and group problem solving by older children.

Kohlberg: Stages In The Development Of Moral Reasoning

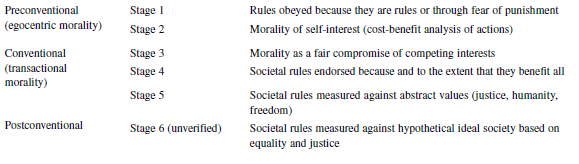

In the 1950s, Lawrence Kohlberg extended Piaget’s approach by constructing a series of moral dilemmas and analyzing subjects’ response to them (see Table 1). Kohlberg identified five stages of reasoning that he claimed characterized all moral development regardless of a person’s beliefs. A sixth stage, proposed as an ideal endpoint of development, has not been verified empirically. The stages are holistic, encompassing all of a person’s judgments, and invariant, with no possibility of regression or skipping stages.

Table 3. Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development

In educational contexts, Kohlberg’s work has prompted efforts to help students advance to higher levels of reasoning. Class discussion of moral dilemmas has indeed been shown to accomplish this, particularly if it is accompanied by extensive peer interaction. Kohlberg, however, became dissatisfied with the discussion approach. He concluded that a context of shared values and democratic procedures would foster development. In the late 1980s, he developed the “just communities”—small schools run democratically—which became a model for a variety of experiments in democratic education.

Gilligan’s Critique Of Kohlberg

In the 1980s, Carol Gilligan pointed out that Kohlberg’s scale was derived from an all-male sample and that female subjects tend to score lower on it. She proposed that girls followed a different developmental path that emphasized care and attachment rather than the abstract principles of justice, which the moral dilemmas elicit.

Gilligan’s claim has received little empirical support. When results of Kohlberg’s studies are controlled for intelligence and educational levels, gender differences disappear. Gilligan’s argument, however, could be reconstructed as a challenge to Kohlberg’s claim that moral development is content-neutral. Even if women’s reasoning is structurally similar to men’s, they might reach different conclusions because of the priority they place on maintaining relationships. Nel Noddings’s ethic of care and Mary Belenky’s connected teaching reflect the popularity of this view among educators.

Kohlberg’s Model: Pro And Con

Other critics have questioned both the cross-cultural validity and the holistic character of Kohlberg’s model. Although cross-cultural studies generally confirm the universality of stages, members of isolated, homogeneous communities score lower than cosmopolitan subjects, leading some scholars to charge ethnocentricity.

With regard to holism, there is substantial evidence that an individual’s reasoning level varies in different contexts. Kohlberg’s defenders have suggested that stages are additive: A subject can still reason at lower levels after progressing to higher levels. This response, however, raises the question of what role reasoning plays in moral agency. If two people act on the same Stage 2 reason, is the one who gives Stage 4 reasons in another context more highly developed? There is, indeed, some evidence that higher-stage thinking is as likely to be associated with rationalization as with moral decision making.

Cognitive developmental theory, in short, provides an excellent account of people’s capacity for moral reasoning, but because of its neglect of action, Kohlberg’s stage model is unsatisfactory as an account of overall moral development.

The Behaviorist Tradition

Behaviorism focuses on observable factors that affect how someone acts. The salient influence is usually other people’s behavior, particularly their positive or negative responses to an agent’s conduct. This system of rewards and punishments, known as reinforcement, could explain transmission of society’s norms, the process that Durkheim envisioned.

This is a constricted view of moral development. If behavior is conditioned by others, then people are like Piaget’s young children—heteronomous, controlled from outside, not truly moral agents at all. They cannot exercise moral judgment. Theories in the behaviorist tradition all confront this challenge.

Bandura And Social Learning Theory

Social learning theorists acknowledge that reinforcement shapes conduct, but they contend that not all learning can be explained in this way. Many grade school students, for example, learn and follow classroom rules without individual punishment or reward.

Albert Bandura introduced the term observational learning to explain this phenomenon. Observational learning includes two elements: first, modeling of behavior by another person and imitation by the learner; second, vicarious experience through reinforcement directed at others. Teachers rely on observational learning when they demonstrate classroom procedures and when they praise attentive children to encourage others to emulate them.

Does observational learning involve moral judgment? The agent must select which behavioral models to imitate and by which vicarious experience to be influenced—a freedom not afforded by direct reinforcement. But does selection involve moral evaluation?

According to Bandura, the selection process involves coding: the reduction of complex events to a few essential features for storage in long-term memory. So, for example, the experience of knowing one’s friend cheated might be remembered as an event involving dishonesty, friendship, and some kind of effect (e.g., anxiety or relief). Depending on the effect, this memory would reinforce either honest or dishonest behavior.

Does coding entail moral judgment? Not necessarily. When a friend cheats, reinforcement effects are influenced by such nonmoral factors as whether the friend is caught, the friend’s emotional state, and what punishment is applied. If the friend pays no penalty, the effect on future behavior might be the exact opposite of what moral judgment would dictate.

Social learning theory explains behavior better than cognitive developmental theory. Research shows that vicarious experience does influence cheating, whereas the role of moral reasoning is unclear. Similarly, a study of people who rescued Jews during the Holocaust found that rescuers did not exhibit more advanced moral reasoning than nonrescuers; what distinguished them was that they lived in “embedded relationships” in which altruistic values were strongly reinforced.

The problem remains, however, that social learning theory explains moral action as the effect of social influence. It shows why people do the right thing, but not why someone would do the right thing for the right reason. Internalization research has attempted to fill this gap.

Internalization Research

Research on internalization of values builds on social learning theory but differs in several important respects. First, unlike learning, internalization occurs only when the agent acts independently, without surveillance or reinforcement. Second, internalization research is not content neutral. Correct, desirable, or worthwhile values are the primary focus. Third, the role of moral judgment is preserved. Social pressure alone can produce compliance, but not willing compliance.

Several different research programs contribute to this field. Attachment research investigates the bond between infant and mother and its effect on development. Parenting-style research examines the effects of authoritarian, authoritative, and permissive parenting on children’s social behavior. Self-determination research focuses on the different ways people adopt beliefs and commitments and how these contribute to healthy functioning. Although the family is a primary unit of interest in this field, research has also been conducted in schools, colleges, churches, and other settings.

Internalization during childhood can be described as a two-person interaction in two stages. In Stage 1, a mentor (parent or teacher) communicates a value to the subject (the child). In Stage 2, the subject decides whether or not to adopt the value and behave accordingly. The factors affecting internalization are characteristics of the mentor, the child, and their interaction.

To communicate effectively, the mentor must be clear, consistent, and sincere and must convey the importance of the issue. Modeling can contribute to the process, but the main emphasis is on explicit teaching and persuasion. Deciding whether or not to act on the value involves two factors: the subject’s motivation and the subject’s judgment of the propriety of the mentor’s intervention.

Motivation can be negative or positive. Threats and power assertion by the mentor provoke resistance; humor and reason assuage it. The mentor can generate positive motivation through warmth, reciprocity, and stimulation of empathy for those affected by the behavior. Judgments of propriety turn on whether the mentor’s value assertion is believable and whether it is perceived as well-intentioned.

Moral judgments appear in Stage 2 of the internalization process. Empathy, an element of motivation, contributes to moral judgment because it focuses on others’ feelings and how one’s action affects them. Deciding whether to believe a value assertion is a judgment about the rightness or wrongness of the action in question. To determine whether the mentor is well-intentioned, one must decide whether it really is important to consider others’ interests rather than only one’s own.

An excellent illustration of how internalization works in a school is Jane Elliott’s brown-eyes blue-eyes experiment, documented in the PBS film A Class Divided. Elliott conducted a role-play exercise to teach third-graders the injustice of racial discrimination, an exercise based on eye color. All of the elements of the model—clarity, sincerity, warmth, reason, and empathy, among others—are clearly visible in the film. In a follow-up discussion, the participants, now adults, reported having acted throughout their lives on lessons learned in that exercise.

This simplified model describes internalization from toddlerhood through early adolescence. Beginning in middle adolescence, the focus shifts from whether to how values are internalized. Self-determination research has identified three distinct styles of internalization. Introjected values are experienced as internal compulsion, a feeling of obligation that is not welcomed and not felt as part of oneself. Values with which one identifies are felt as part of oneself, but not as an essential part, because they are not integrated with other aims. Integrated values are experienced as an essential part of oneself, values one could not reject and still be the same person. Integrated values are most stable and conducive to healthy functioning. In general, with appropriate developmental adjustments, the factors that promote internalization in childhood promote integrated internalization in adolescence and adulthood.

Internalization, in short, maintains the focus on moral action characteristic of the behaviorist tradition, yet also makes a place for moral judgment. In this respect, it is the most comprehensive of the accounts of moral development reviewed here. Not surprisingly, it is also the most complex. The child’s moral development depends not just on reasoning capacity or environmental cues, but also on relationships, social context, and the child’s sense of independence and self-efficacy.

Does internalization offer a complete account of moral development? Does integrated internalization— the adoption and consolidation of values—represent achievement of moral agency? Some might object that integrated internalization places values beyond critical scrutiny and thus represents a restriction of agency rather than its culmination. One could argue, however, that the model does require scrutiny of values before internalization and also that adult moral agents do face restricted options, because they do not allow themselves to act contrary to conscience.

Research Support

The behaviorist and cognitivist traditions both have empirical support. Their central tenets—that reasoning and external influences contribute to moral development—could both be true at the same time. Convergent tendencies in these traditions reinforce their compatibility. Kohlberg’s just community experiments tacitly concede that external influences shape moral reasoning, and thus social learning affects moral development. The prominence of reason in internalization models concedes that Kohlberg’s research is not irrelevant to moral behavior.

The competing theories and heterogeneous research clearly establish that achievement of full moral agency is a complex process. The journey begins early in life and takes a long time to complete. A great many institutions and aspects of education affect the outcome. Much is known about some of these influences on education, such as parenting styles, attachment, and effects of discussion on levels of moral reasoning. About others, knowledge is rudimentary. Internalization research, building on Bandura’s work and borrowing from Kohlberg’s, has given us a very general and somewhat tentative model of moral development, but even a cursory review of the educational applications makes clear that there is a great deal more to be learned.

Bibliography:

- Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2002). Handbook of self-determination research. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

- Durkheim, E. (1961). Moral education. Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

- Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Grusec, J. E., & Kuczynski, L. (Eds.). (1997). Parenting and children’s internalization of values: A handbook of contemporary theory. New York: Wiley.

- Kohlberg, L. (1981). The philosophy of moral development: Moral stages and the idea of justice. San Francisco: Harper & Row.

- Noddings, N. (1992). The challenge to care in schools: An alternative approach to education. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Oliner, S. P. (1992). The altruistic personality: Rescuers of Jews in Nazi Europe. New York: Free Press.

This example Moral Education Essay is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need a custom essay or research paper on this topic please use our writing services. EssayEmpire.com offers reliable custom essay writing services that can help you to receive high grades and impress your professors with the quality of each essay or research paper you hand in.