Political parties have been described as the core institutions of democracy and necessary for its flourishing. Such claims echo earlier statements about democracy as unthinkable without parties. Even if the way in which parties function has received severe criticism, there is also a widespread consensus that parties are necessary and that it is difficult to imagine democracy without them. Hence, representative democracy has become the norm and a decline of parties is seen as detrimental to democracy.

Understanding of what is meant by a party must be established before entering the debate on whether and how parties have changed. A minimal concept of a party entails a certain level of organization, a more or less coherent program, and a procedure to select representatives. A number of functions can then be added to this. These, however, are not strictly necessary to speak of a party, yet this does not imply that a party is explained from the functions performed, or its absence if certain functions are not performed. Most authors mention recruitment, aggregation, and mobilization as functions. In addition, parties have to find a balance between the goals of votes, office, and policy. This would mean that a party typically is defined by these goals simultaneously: winning elections, gaining representation, and being in government.

Defining Parties And Their Functions

One of the oldest and most famous definitions of party is that of Edmund Burke: “Party is a body of men united for promoting by their joint endeavours the national interest upon some particular principle in which they are all agreed” (40). Burke importantly assumes that parties strive for the same goals (i.e., the national interest), and only differ on the policies to achieve this. Taking this one step further, Anson Morse argues that a party advances “the interests and realization of the ideals, not of the people as a whole, but of the particular group which it represents” (91). Hence, contrary to Burke, Morse claims that parties pursue their own objectives. These objectives are, first, distinguishing themselves from their competitors and, second, gaining a large share of the popular vote.

The well-known critiques of parties from Moisey Ostrogorski and Robert Michels give another twist to this debate on general versus specific interests. Both authors focus in particular on how parties operate as organizations and with what effects. Michels’s description of the elitist and oligarchical tendencies within parties, or Ostrogorski’s depiction of the vicious influence of the party “machine” and the caucus imply that parties evolve in such a way that the interests of the masses make way for the particularistic and narrow interests of the few.

After World War II (1939–1945), the discussion on the nature of parties reemerged, but it was more oriented toward conceptualization—especially the necessary features to speak of a party. This led to various typologies of parties and party models. For instance, Otto Kirchheimer’s catch-all concept largely focused on the characteristics of mass parties, whereas Maurice Duverger distinguishes between membership parties and cadre parties. More recently, other types of parties have been put forward, like cartel parties and business-firm parties, where membership is less important and resources are derived from state subsidies or individual donations.

Joseph La Palombara and Myron Weiner define parties by a certain level of organization (locally and nationally) and by their office-seeking and vote-seeking characteristics. They distinguish the modern party from the “cliques, clubs and small groups of notables” (8) that can be identified as the antecedents of the modern political party. This combination of organization and programmatic goals is also found in Richard Rose’s work, identifying a party as “an organization concerned with the expression of popular preferences and contesting control of the chief policy-making offices of government” (3).

This conceptual and empirical development tends to blur the difference between what parties are and what parties do. A party will thus be defined here as an organized group of people who select candidates for parliament or government by participating in elections. This is the main function, or task, that sets parties apart from social movements, trade unions, or interest groups. Parties may perform all other functions, but they are not exclusive for a party.

Party Functions

In his discussion of the role of parties in the political system, Morse distinguishes two main functions of political parties: the education and organization of public opinion, and the administration of government. Moreover, he introduces what has later become known as the linkage function of parties, or the integration of interests. His contemporary, Lord Bryce, distinguishes five functions. All parties share four of these functions: union (keeping the party together), recruitment (bringing in new voters), enthusiasm (exciting and rousing voters), and instruction (informing and educating voters). Interestingly, Bryce argues that a fifth function, the selection of party candidates, is rather unimportant for European parties, while it is central to American parties.

In the classic article, “Political Parties in Western Democracies,” Anthony King provides an authoritative overview of the debate on party functions. Whilst being critical toward the functionalist approach, he does not suggest to do away with the study of functions altogether, but rather turns this into an agenda for empirical research. King’s main problem with functionalism is that parties are considered to produce consequences, and this has two main flaws. First, if certain hypothesized consequences are absent, one might believe that the party is not present. Second, there is the risk of inferring the existence of a party from the presence of the consequences—a general critique of functionalism.

The literature in the years that followed King’s contribution focuses less on party functions, but rather on the empirical study of how political parties performed in terms of vote-seeking, office-seeking, and policy-seeking actors within representative democracies.

Empirical Developments

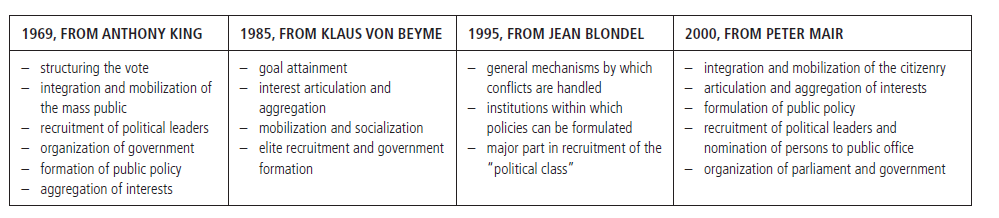

In spite of these critical notes, party functions have remained central to analyzing parties. In fact, many authors have incorporated the objections raised, but as Russell Dalton and Martin Wattenberg argue, it is a functional rather than a functionalist approach. Party functions are used to measure what parties do, but functions are not seen as the constituting or defining elements of what a party is. Party functions become tools to measure change, transformation, or adaptation of parties, thus following King in his advice not only to draw up a list of party functions, but also to critically examine if and when parties carry out these functions. Table 1 presents an overview of the functions that several authors have ascribed to parties.

Table 4: Overview Of Party Functions From 1969 To 2000

Table 1 illustrates considerable overlap with King’s functions, but none of these amounts to as many as six functions. This is no surprise: if the environment of parties changes, new functions may emerge while others become less relevant. One example of this is the education, or information, function, which was crucial for scholars at the end of the nineteenth century, then moved into the background for a long period, but recently reappeared in a different form in an era of mass media and modern technology.

Jean Blondel’s inventory has a slightly different presentation: rather than identifying functions, it basically describes group characteristics. Blondel speaks of mechanisms and institutions and refers to specific tasks that parties fulfill: handling conflicts and formulating policies. This inventory is parsimonious, as it leaves out specific reference to vote structuring, mobilization, and organization of government. Peter Mair stays closest to King’s inventory: aggregation of interests combines with articulation, the role of parties expands to the organization of both parliament and government, and nomination of persons to public office is added to the recruitment function. The main difference is that Mair, like several others, leaves out the function of “structuring the vote.”

On the whole, there is a striking congruence from the 1960s onwards. Most scholars assume that parties still perform roughly the same functions as they did thirty or forty years ago, even if the balance between these functions may have altered. On the basis of this overview, there are three essential functions:

- integrating and mobilizing the citizens to vote

- recruiting a political class to govern

- articulating and aggregating societal interests

This list contains functions related to both representation and governance, while it also refers to the tasks of a party in policy making and during elections. The functions emphasize the link between parties and voters, and the competition between parties. Finally, they allow for comparative analysis over time and across countries.

How Parties Develop: Decline Versus Transformation

A perennial debate concerns how parties have developed and continue to be omnipresent in Western democracies. Moreover, in many countries, parties have also been instrumental in the transition toward democracy and in providing legitimacy after its establishment. As Stefano Bartolini and Mair describe it, parties are important within a democratic political system since they concurrently “control political behaviour and harmonize different institutional orders” (342). In addition, the authors see no credible alternative to parties, which begs the question of what happens to democracy if parties no longer perform this political and institutional integration. After 1945 parties were regarded as indispensable for making democracy work.

The general idea that parties are essential for democracy still stands fast. Ian Budge and Hans Keman consider parties the “irreducible core” of democracy. José Montero and Richard Gunther state that parties are “essential for the proper functioning of representative democracy” (3), and they cite a number of other recent publications that put forward comparable claims. In other words, parties and democracy are seen as inseparable. A possible decline of parties—especially if this concerns functions of representation considered essential for making democracy work—is then often seen as a “crisis” of democracy. The often observed lower levels of trust in parties indicates this decline.

The Question Of Party Decline

Montero and Gunther point at a paradox in the party literature: an increased attention for parties at the end of the 1990s accompanies a claim that parties are in decline. Another interesting point is that writings on party “crisis” mainly stem from the United States. American scholars such as Tim Aldrich have been more alert in this respect, contrary to scholars in Western Europe. Yet, Hans Daalder in 1992 mentions possible causes of party decline as:

- The legitimate role of parties is questioned, since they are considered counterproductive (in problem solving by policy making that reduces “good governance”).

- Selective perception of party competition: certain party systems are considered “good,” others “bad.”

- Redundancy of party: parties become irrelevant as other actors or institutions (e.g., interest mediation and representation) take over their functions.

In summary, it is argued that parties cannot exist or ought not exist (anymore).The first line of reasoning relates to what Daalder labels the redundancy of parties, while the second is seen as a result of distrusting parties.

These arguments come together in Joachim Raschke’s claim that the limits of what parties can do have been reached and that there is party “failure” in various aspects. First, there is over adaptation, and parties are not vehicles for change but enhance the status quo. Second, overgeneralization causes parties to no longer represent specific interests. Third, over institutionalization broadens the gap between citizens and parties. This party failure would explain the lower rates of electoral participation and of dealignment of voters across Europe and the United States.

Likewise, Mair’s analysis narrows the central aspects of party change to identity and functions. He argues that how parties present themselves to the electorate and the way they compete makes it increasingly difficult for voters to find ideological differences, or understand how these differences relate to their own interests. For the second element, party functions, Mair makes distinguishes representative and procedural functions and argues that the former type of functions—integrating and mobilizing the citizenry, articulating and integrating interests, and formulating public policy—have been drastically reduced. Conversely, the procedural functions—recruitment of candidates for office, organization of parliament and government— have remained important and may even gain significance. Thus, parties are changing from representative agencies into governing agencies: they have become parties of the state and are less part of society.

Aldrich considers the problem as emanating from a paradox where parties no longer match collective choice and related action by means of collective decision making. In the eye of the public and electorate, a party becomes redundant because they view “parties [that] are designed as attempts to solve problems that current institutional arrangements do not solve and that politicians have come to believe they cannot solve” (22). Hence, parties and their representatives are no longer capable to represent or to govern.

The conclusion can be drawn that the term party crisis concerns, in particular, the representative functions of parties. First, parties are less relevant for the information, education, and mobilization of the electorate. The role of cyberspace is but one example of how new technologies absorb this function. Second, parties are less successful in integrating interests. This problem relates both to the apparent inability of parties to adapt to new societal concerns and demands for other forms of participation, and the vanishing of ideological differences. Third, this development reinforces electoral volatility in many countries and points to processes of dealignment and realignment of individual voters vis-à-vis established parties or even departing from political life altogether.

Party Adaptation And Survival

There are three flaws in the debate surrounding party crisis, or party decline. First, using the term party crisis implies a view on what a party is, or a standard against which parties can be judged. Yet, it is unclear what this standard should be, and whether or not such a standard might well be contextually dynamic. Paul Webb qualifies the arguments about party crisis in a very succinct way:

In the absence of compelling systematic evidence that parties’ scope for autonomous action has diminished we would argue that most probably there never was a Golden Age of party government, and that it is therefore a misconception to speak in terms of “party decline” in this respect. (447)

Research on party crisis or decline should therefore start with a conscientious inventory of the roles and functions parties play As Dalton and Wattenberg have argued in their “functional approach to party politics,” certain functions may indeed have eroded, but this is compensated for by gaining others. Many authors tend to link the citizenry with the state as the crucial function of parties and from such a perspective, any loosening of this linkage is seen as decline. Yet, considering all party functions equal implies that a shift from representative functions to recruitment and governance is not the same as decline. Katz and Mair show that the main drawback of this perspective is that relations between parties and the state are ignored. Speaking of decline or failure is misconceived, and they see change as few signs that the role of parties has really diminished.

The third flaw in this type of reasoning is its emphasis on stability: it suggests that a party should remain more or less the same over time. Yet, the ability to change and adapt—to attract new groups of voters, to change the internal organization, or to renew the party ideology—can also be seen positively. This is Klaus von Beyme’s functional efficiency argument: parties have been able to adapt their organization and role to new circumstances. In a traditional view—putting the citizen-party linkage at the center—this is, however, seen as party decline. Trends of increasing electoral volatility and decreasing membership demonstrate that fewer people identify strongly with one particular party, and that voters are increasingly volatile. Yet, calling this party decline is biased toward the status quo.

Several other authors have also consistently qualified the arguments of party crisis or party decline. Daalder is therefore right in warning against writing off parties too hastily, and he makes a plea in favor of analyzing their actual functions and how these may change. The challenge is to understand to what extent there is a response to external factors and in how far it signifies a deliberate strategy of parties. Thus, the adequate picture that emerges is not so much crisis or decline, but rather a transformation of how parties shift attention to different functions.

A potential answer to the question of party survival is offered by the cartel thesis. Katz and Mair contend that the problem of the literature on party crisis and party survival stems from the questionable assumption that parties should be “classified and understood on the basis of their relationship with civil society” (93). Parties move away from civil society and become part of the state, which is the vital point of the cartel model.

Probably the best way to describe the process behind the survival and adaptation of parties is proposed by Von Beyme’s institutional efficiency. Some parties may disappear, other parties may emerge, but the organizations as such and the party systems in which they function stay put. Hence, both functional and evolutionary arguments are acknowledged: parties are necessary for the functioning of democracy, and they manage to adapt to new circumstances.

Bibliography:

- Aldrich,Tim. Why Parties? The Origin and Transformation of Party Politics in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

- Bartolini, Stefano, and Peter Mair. “Challenges to Contemporary Political Parties.” In Political Parties and Democracy, edited by Larry Diamond and Richard Gunther, 327–343. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001.

- Blondel, Jean. Comparative Government: An Introduction. 2nd ed. London: Prentice Hall, 1995.

- Bryce, James. “Party Organizations.” In Perspectives on Political Parties: Classic Readings, edited by Susan E. Scarrow, 233–238. Basingstoke, U.K.: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002.

- Budge, Ian, and Hans Keman. Parties and Democracy: Coalition Formation and Government Functioning in Twenty States. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

- Burke, Edmund. “Thoughts on the Cause of the Present Discontents.’ In Perspectives on Political Parties: Classic Readings, edited by Susan E. Scarrow, 37–43. Basingstoke, U.K.: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002.

- Daalder, Hans. “A Crisis of Party?” Scandinavian Political Studies 15, no. 4 (1992): 269–288.

- Dalton, Russell J., and Martin P.Wattenberg, eds. Parties without Partisans: Political Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Duverger, Maurice. Political Parties:Their Organization and Activity in the Modern State. London: Methuen, 1959.

- Gunther, Richard, José R. Montero, and Juan J. Linz, eds. Political Parties: Old Concepts and New Challenges. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Katz, Richard S., and Peter Mair. “Changing Models of Party Organization and Party Democracy:The Emergence of the Cartel Party.” Party Politics 1, no. 1 (1995): 5–28.

- King, Anthony. “Political Parties in Western Democracies.” Polity 2, no. 2 (1969): 111–141.

- Kirchheimer, Otto. “The Transformation of Western European Party Systems.” In Political Parties and Political Development, edited by Joseph G. LaPalombara and Myron Weiner, 177–200. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1966.

- LaPalombara, Joseph G., and Myron Weiner. “The Origin and Development of Political Parties.” In Political Parties and Political Development, edited by Joseph G. LaPalombara and Myron Weiner, 3–42. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1966.

- Mair, Peter. “Partyless Democracy: Solving the Paradox of New Labour? New Left Review 2, no. 2 (2000): 21–35.

- “Political Parties and Party Systems.” In Europeanization: New Research Agendas, edited by Paolo Graziano and Maarten Vink. Basingstoke, U.K.: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

- Michels, Robert. Political Parties: A Sociological Study of the Oligarchical Tendencies of Modern Democracy. New York: Collier Books, 1962.

- Montero, José R., and Richard Gunther. “Introduction: Reviewing and Reassessing Parties.” In Political Parties: Old Concepts and New Challenges, edited by Richard Gunther, José R. Montero, and Juan J. Linz, 1–35. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Morse, Anson D. “The Place of Party in the Political System.” In Perspectives on Political Parties: Classic Readings, edited by Susan E. Scarrow, 91–98. Basingstoke, U.K.: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002.

- Puhle, Hans-Jürgen. “Still the Age of Catch-allism? Volksparteien and Parteienstaat in Crisis and Re-equilibration.” In Political Parties: Old Concepts and New Challenges, edited by Richard Gunther, José R. Montero, and Juan J. Linz. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Raschke, Joachim. “Political Parties in Western Democracies.” European Journal of Political Research 11, no. 1 (1983): 109–114.

- Rose, Richard. The Problem of Party Government. London: Macmillan, 1974.

- Schattschneider, Elmer E. Party Government. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1942.

- Von Beyme, Klaus. Political Parties in Western Democracies. Aldershot, U.K.: Gower, 1985.

- Webb, Paul. “Conclusion: Political Parties and Democratic Control in Advanced Industrial Societies.” In Political Parties in Advanced Industrial Democracies, edited by Paul Webb, David M. Farrell, and Ian Holliday. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

This example Political Parties Essay is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need a custom essay or research paper on this topic please use our writing services. EssayEmpire.com offers reliable custom essay writing services that can help you to receive high grades and impress your professors with the quality of each essay or research paper you hand in.