This example African Politics And Society Essay is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need a custom essay or research paper on this topic please use our writing services. EssayEmpire.com offers reliable custom essay writing services that can help you to receive high grades and impress your professors with the quality of each essay or research paper you hand in.

Throughout this entry, Africa refers to sub-Saharan Africa, the region south of the Saharan Desert that is bounded in the north and west by Mauritania; in the east by Eritrea, Ethiopia, Sudan, and Somalia; and in the south by the Republic of South Africa.

The contemporary political history of Africa is marked by imperialism, the expulsion of foreign powers and settler elites, and the post-independence travails of its roughly fifty states.

Imperialism

Africa was among the last regions of the globe to be subject to imperial rule. In the so-called scramble for Africa, as described by Thomas Pakenham in his 1991 book of that title, the British and French seized major portions of the continent; Belgium, Germany, Italy, Portugal, and Spain seized lesser holdings as well. During the imperial era, most of Africa’s people were subject to the rule of bureaucrats in London, Lisbon, and Paris rather than being ruled by leaders they themselves had chosen. Two states in Africa had long been independent: Ethiopia from time immemorial and Liberia since 1847. In 1910, the settlers of South Africa succeeded in securing independence from British bureaucrats.

European immigrants settled in several territories: Kenya in the east, the Rhodesias in the center, and portions of southern Africa. Conflicts between the settler populations and colonial bureaucrats characterized the politics of the colonial era, as white settlers strove to control the colonial governments of these colonies and to dominate their native populations.

While Africa’s peoples fought against the seizure of their territories, they lacked the wealth, organization, and weaponry to prevail. The situation changed, however, during World War I (1914–1918) and World War II (1939–1945).The wars eroded the capacity and will of Europeans to occupy foreign lands, while economic development increased the capacity and desire of Africa’s people to end European rule.

During World War II, the allied powers maintained important bases in Africa, some poised to support campaigns in the Mediterranean and others to backstop armies fighting in Asia. After World War II, the colonial powers promoted the development of African export industries, seeking thereby to earn funds to repay loans contracted with the United States to finance the war. The increase in exports led to the creation of a class of prosperous farmers and the rise of merchants and lawyers who provided services to the export industries. As World War II gave way to the cold war, the United States began to stockpile precious metals and invested in expanding Africa’s mines, refining its ores, and transporting its precious metals overseas. That Africa’s economic expansion took place at the time of Europe’s decline prepared the field for its political liberation. The one was prospering while the other was not, and their relative power shifted accordingly.

Nationalist Revolt

Among the first Africans to rally against European rule were urban elites, whose aspirations were almost immediately checked by resident officials of the colonial powers. Workers who staffed the ports and railways that tied local producers to foreign markets soon joined them. In the rural areas, peasants rallied to the struggle against colonial rule, some protesting intensified demands for labor and the use of coercion rather than wage payment to secure it. Among the primary targets of the rural population were the chiefs, who had been tasked by colonial rulers with taxing the profits of farmers and regulating the use of their lands. Thus did the Kenya Africa Union support dock strikes in Mombasa and the intimidation of chiefs in the native reserves. Similarly, the Convention Peoples’ Party backed strikes in the Gold Coast (now Ghana) port cities of Tema and Takoradi, while seeking to “destool” chiefs inland.

Adding to the rise of nationalist protest was global inflation. Reconstruction in Europe and rearmament in the United States ran up against shortages of materials and higher prices in global markets. Throughout Africa and the developing world, consumers rallied to protest against these increases, tending to blame them on European monopolies—such as in Ghana, where the people focused their anger on the United Africa Company—or local trading communities—such as the Indian merchants in Kenya or Lebanese traders in Sierra Leone.

The economic development of Africa thus transformed the social composition and political preferences of its people. It was in the postwar period, however, that independence was achieved by the vast majority of Africa’s people. At first, political liberty arrived in a trickle—to the Sudan in 1956 and Ghana in 1957. Soon thereafter independence came as a flood, with twenty-nine Frenchand English-speaking states securing independence from 1960 to 1965, the Portuguese territories in the mid-1970s, and the settler redoubts of southern Africa in the last decades of the twentieth century.

The Postindependence Period

The optimism of the nationalist period very quickly gave way to pessimism, as governments that had seized power turned authoritarian or were displaced by military regimes. Ghana’s experience was emblematic of this early postindependence trend. Ghana had been among the first African countries to attain self-governance (1954) and then independence (1957). Both events were celebrated not only in Africa but throughout the globe. In 1960, a change in the constitution gave Kwame Nkrumah, as head of state, the power to dismiss civil servants, judges, and military officers without the authorization of parliament. In 1963, the president acquired the power to detain persons charged with political crimes and to try their cases in special courts. When, in 1964, Nkrumah proclaimed the ruling party the sole legal party in Ghana, he both followed and gave impetus to the trend toward single-party rule on the continent. When, in 1966, Ghana’s military toppled the Nkrumah regime, Ghana joined Sudan, Benin, Togo, and the Central African Republic—all states in which the national military had overthrown a civilian regime (in 1958, 1962, 1963, and 1965 respectively). Following the military’s overthrow of Nkrumah’s government in Ghana, armed forces drove civilian governments from power in Burkina Faso, Nigeria, and Burundi in 1966, and Congo in 1968. By the mid-1970s, the military held power in one-third of the nations of sub-Saharan Africa.

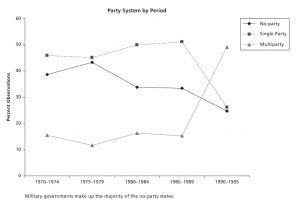

By the mid-1970s, the politics of Africa had turned authoritarian. Only four states in Africa—Botswana, Gambia, Mauritius, and Senegal—retained multiparty systems. Figure 1 captures this turn to authoritarianism in postindependence Africa.

Late-Century Politics

The politics of late-century Africa was marked by two major trends. The first was the return to multiparty politics; the second, an increase in political violence. These trends had common origins in global political and economic crises.

Figure 1: Military governments make up the majority of the no-party states.

Beginning with the rise in oil prices following the Yom Kippur war of 1973, the economies of the advanced industrial nations fell into deep recession. As a result of declining growth in these nations, Africa’s export earnings declined. Private income fell, and so too did government revenues.

Some economies initially eluded economic decline: those that produced oil, of course, and others that produced crops, such as coffee, whose prices rose when frost and war drove two major exporters from global markets. Those countries blessed with rich natural endowments—Zambia, with its copper deposits, or Zaire, with copper, cobalt, and gold— could borrow and thus postpone cuts in spending. In the mid-1980s, their incomes also collapsed. In the early 1980s, the U.S. Federal Reserve had precipitously increased the rate of interest, sharpening the level of recession. The subsequent collapse of the Mexican peso led to an end of private lending to developing economies. When in 1986 Arab countries increased oil production in an effort to revive the growth of the industrial economies, Africa’s oil exporters experienced a decline in earnings. With this last blow, virtually all the economies of the continent fell into recession.

In the recession, Africa’s citizens experienced increased poverty; so too did their governments. The result was a decline in the quality of public services. Most African governments secured their revenues from taxes on trade. Given the decline in exports, they could respond to the fall in revenues either by freezing salaries and cutting their payrolls or by running deficits, which lowered the real earnings of public servants by increasing prices. Children attended schools that lacked text books. Teachers were often absent, seeking to supplement their salaries with earnings from private trade. In clinics and hospitals, patients suffered from the lack of medicines and the absence of staff. Soldiers went unpaid.

In response, the citizens of Africa began to turn against their governments. Parents and children protested the decline in the quality of schools, hospitals, and clinics. Business owners targeted the erratic supply of water and electricity and the crumbling systems of transport and communications. Discontent with the decline in public services was heightened by the disparity in fortunes between those with power and those without. High-ranking officials could send their children to schools abroad or secure medical treatment in London, Washington, or Paris. The political elite could recruit and pay their own security services, purchase private generators, and maintain private means of transport. In general, those who ruled could escape the misery that befell others. As the economies of African states collapsed, citizens increasingly called for reform, particularly the restoration of multiparty politics and an increase in the power of the masses relative to the power of those who governed.

Opposition to Africa’s authoritarian regimes also mounted from abroad. Governments had fallen into debt, and foreign creditors increasingly demanded that the governments adopt reform policies aimed at reigniting economic growth on the continent. Governments that were accountable to their people, the creditors argued, would be less likely to prey upon private assets, distort private markets, and favor public firms over private enterprises. Led by officials of the World Bank, economic technocrats began to join with local activists in demanding political reform.

In the later decades of the twentieth century, Africa’s political elites thus faced challenges from home and abroad. To a remarkable degree, military and single-party regimes proved able to hold onto power until a second global shock—the fall of communism—destabilized many African regimes. Western governments had tolerated repressive practices in Africa nations in exchange for support in the cold war, but after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Western governments no longer urged their economic technocrats to release loans to repressive governments. They were willing to let fall those African elites whose services they no longer required.

In response to increased pressures from home and abroad, some governments reformed. As shown in Figure 1, whereas more than 80 percent of Africa’s governments had been no party (largely military) or single-party systems in the mid-1980s, by the mid-1990s, multiparty systems prevailed in nearly one-half of African countries. Other governments, however, reacted by intensifying the level of repression. In Togo, the armies of President Gnassingbé Eyadéma fired on civilians who had gathered in the streets of Lomé, the national capital, to protest his rule. In Liberia, Rwanda, and Sierra Leone, thugs hired by the governing parties harassed and harried those who sought to displace them. In Burundi, the military, once displaced from power, slaughtered the civilians who had seized it, while in neighboring Rwanda, the government unleashed a program of mass killing, seeking to eradicate those who opposed it.

Since the late twentieth century, military coups have become rare, and multiparty elections the norm in Africa. In addition, the continent has become more peaceful, with civil wars ending in Angola, Burundi, Liberia, Mozambique, Rwanda, Somalia, and, less certainly, Congo. In the mid-1990s, economic growth returned for the first time since the 1980s, apparently sparked by the increased demand for primary products resulting from economic growth in China and India, as well as the return of private investment, much by companies from South Africa. When measured in terms of peace and prosperity, however, the nations of Africa still occupy the lower rungs of the global community. For the first time in several decades, there have been distinct signs of political and economic progress in the continent.

Ethnicity

Some have attributed Africa’s slow growth to ethnic diversity; others attribute its political instability to conflict among ethnic groupings. Many observers thus contend that ethnicity is at the roots of Africa’s development crisis.

The evidence, however, suggests several flaws in this argument. Though some argue that ethnic diversity weakens the capacity of people to agree on the allocation of shared resources, others argue that ethnic groups mobilize resources in support of their communities by, for example, sponsoring the educations of promising young people, building schools and clinics, and conferring recognition on those who use their wealth in support of their communities. There are large literatures on the local funding of schools in Kenyan communities and of the funding of scholarships by Ibo communities in eastern Nigeria. In addition, while ethnic groups may compete for power, in most African nations this competition is peaceful. As in the urban centers of the advanced industrial countries, politics in Africa may pit one ethnic group against another, but these rivalries, while colorful, rarely lead to violence.

Recent research suggests the conditions under which conflicts among ethnic groups can become violent. One such condition occurs when small groups capture power and employ it to extract wealth from others. Such was the case in Burundi under the rule of Michel Micombero or in Liberia under Samuel Doe. To remain in power, such groups may have to rule by fear, thereby cowing or decimating their political opposition. In addition, when one ethnic group is sufficiently large to form a political majority on its own, others may come to fear the prospect of political exclusion and so choose to revolt, as did the Tutsi in Rwanda and the Gio and Mano in Liberia. The statistical evidence for this phenomenon is not robust in cross-national data, but qualitative accounts and data on within country variation offer fairly consistent support for it.

In Africa, as elsewhere, normal politics involves the management of differences among ethnic groups. Only in special circumstances do political forces align so as to transform these rivalries into political violence.

Bibliography:

- Abernethy, David B. The Dynamics of Global Dominance: European Overseas Empires, 1415–1980. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2000.

- Austin, Dennis. Politics in Ghana, 1946–60. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1964.

- Bates, Robert H. Essays on the Political Economy of Rural Africa. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987.

- Open Economy Politics. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1997.

- When Things Fell Apart: State Failure in Late-century Africa. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Bates, Robert H., and Irene Yackovlev. “Ethnicity, Capital Formation, and Conflict: Evidence from Africa.” In The Role of Social Capital in Development: An Empirical Assessment, edited by Christiaan Grootaert and Thierry Van Bastelaer, 310–340. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Collier, Paul. “The Political Economy of Ethnicity.” In Proceedings of the Annual Bank Conference on Development Economics, edited by B. Pleskovic and J. E. Stigler, 387–399.Washington D.C.: World Bank, 1999.

- Collier, Paul, Robert H. Bates, A. Hoeffler, and Steve O’Connell. “ Chapter 11: Endogenizing Syndromes.” In The Political Economy of African Economic Growth, 1960–2000, edited by B. Ndulu, Paul Collier, Rorbert H. Bates, and Steve O’Connell. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Collier, Ruth Berins. Regimes in Tropical Africa: Changing Forms of Supremacy, 1945–1975. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982.

- Easterly, William, and Ross Levine, “Africa’s Growth Tragedy: Policies and Ethnic Divisions.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 112 (November 1997): 1203–1250.

- Fearon, James D., and David D. Laitin. “Ethnicity, Insurgency and Civil War.” American Political Science Review 97 (February 2003): 75–90.

- Hodgkin, Thomas. Nationalism in Colonial Africa. New York: New York University Press, 1956.

- Kaplan, Robert D. “The Coming Anarchy.” The Atlantic Monthly 273 (February 1994): 44–76.

- Meredith, Martin. The State of Africa: A History of Fifty Years of Independence. London: Free Press, 2005.

- Miguel, Edward, and Mary Kay Gugerty. “Ethnic Diversity, Social Sanctions, and Public Goods in Kenya.” Journal of Public Economics 89, no. 11–12 (2005): 2325–2368.

- Murshed, S. Mansoob, and Scott Gates. “Spatial-Horizontal Inequality and the Maoist Insurgency in Nepal.” Paper comissioned by the Department for International Development, London, 2003.

- Pakenham, Thomas. The Scramble for Africa: The White Man’s Conquest of the Dark Continent from 1876 to 1912. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1991.

- Uchendu, Victor C. The Igbo of Southeast Nigeria. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1965.

- World Bank. Sub-Saharan Africa: From Crisis to Sustainable Growth. Washington, D.C.: World Bank, 1989.

- Governance and Development. Washington, D.C.: World Bank, 1991.

See also:

- How to Write a Political Science Essay

- Political Science Essay Topics

- Political Science Essay Examples