This example Corruption And Other Political Pathologies Essay is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need a custom essay or research paper on this topic please use our writing services. EssayEmpire.com offers reliable custom essay writing services that can help you to receive high grades and impress your professors with the quality of each essay or research paper you hand in.

In an ideal democracy, the polity faithfully maps the preferences of citizens into public choices. Protections for individual rights constitutionally limit the range of democratic choice, but within those constraints, citizens’ preferences rule. In practice, real governments fail to measure up. Some of this divergence is the result of disagreements among citizens over policy; other difficulties arise from the nature of representative government. If preferences diverge, the state must aggregate preferences to make choices using methods that are subject to strategic manipulation and that produce winners and losers. This will happen even in a direct democracy lacking any of the institutions of the modern state beyond elections. Furthermore, most democratic states require representative institutions in order to function, and under these structures some will have more power than others because of their geographical locations or their strategic positions. These are not pathologies but are, instead, inherent in the structure of representative government.

Such difficulties, which need to be acknowledged and managed, are distinguishable from others that represent direct challenges to the legitimacy of governments, however democratic their nominal structure. The tendency of political systems to provide narrowly focused goods and services, pork barrel projects, is a familiar complaint about democracy, but it is not pathological. It is the inevitable result of a political system that elects representatives from single-member districts. These representatives will try to satisfy the local demands of their constituents as well as work for broader public goals. Two types of political pathologies are, however, of concern: corruption and clientalism. The former involves the illicit personal enrichment of public officials, often combined with excess profits for those who pay bribes. The latter is a more subtle phenomenon occurring when public officials provide benefits to their supporters in a way that undermines general public values. As Jana Kunicová and Susan Rose-Ackerman argue in their 2005 article, past work has too often conflated pork barrel politics, clienteles, and corruption. It is important, however, to analyze them as separate, if overlapping, phenomena. For example, structural reforms designed to limit pork barrel politics may lead to higher levels of illegal corruption that diverts public money and power to the private benefit of politicians and their corrupt supporters.

The focus here is on states that have not descended into chaos and anarchy. States where corruption, clientalism, and other political pathologies are endemic may, of course, eventually collapse, but sometimes such states are quite stable and long lasting. As Robert Rotberg argues, the system may be pathological in the sense of not reflecting the interests of most citizens and of not providing security, but it does endure.

The line between pathology and normal democratic politics is not always easy to draw. Extreme cases are easy to identify—Zaire under the thirty-two year presidency of Mobutu Sese Seko, Cambodia under Khmer Rouge leader Pol Pot— but what should we make of democratic states where private wealth has a major impact on public choices? How much of this is the normal and predictable result of the fact that elections cost money, and when does the use of private funds to support political careers become corrupt or pathological? When is support for public works in one’s home district an indication that a representative system is working well, and when does it tip over the line into dysfunctional clientalism?

In a political system that pays lip service to notions of public accountability and is, in fact, controlled by corrupt officials, the basic problem is the interaction between officials’ venality and corrupt inducements offered by private groups and individuals. Alongside alternative models of corrupt public and private interactions, the more familiar case of a functioning democracy is, nevertheless, deeply influenced by clientelistic networks and concentrations of private wealth.

Corruption

Corruption describes a relationship between the state and the private sector. Sometimes state officials are the dominant actors; in other cases, private actors are the most powerful forces. The relative bargaining power of these groups determines both the overall impact of corruption on society and the distribution of the gains between bribers and bribe payers. The nature of corruption depends not just on the organization of government but also on the organization and power of private actors. A critical issue is whether either the government or the private sector has monopoly power in dealing with the other.

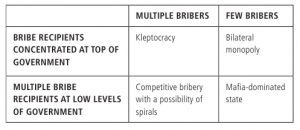

In Corruption and Government: Causes, Consequences and Reform (1999), Susan Rose-Ackerman distinguishes between kleptocracies, where corruption is organized at the top of government, and other states, where bribery is the province of a large number of low-level officials. On the other side of the bribery “market,” there is a difference between cases with a small number of major corrupt private actors and ones where the payment of bribes is decentralized across society. Table 1 from Rose-Ackerman’s book illustrates four polar cases: kleptocracy, bilateral monopoly, mafia-dominated states, and competitive bribery.

Kleptocracy

In the extreme case of a kleptocratic ruler who faces a large number of unorganized potential bribe payers, a powerful head of government can organize the political system to maximize its corrupt extraction possibilities. According to American economist and social scientist Mancur Olson in his 1993 article “Dictatorship, Democracy and Development,” such a “stationary bandit” acts like a private monopolist, striving for productive efficiency, but restricting the output of the economy to maximize profits. The ruler sacrifices the benefits of patronage and petty favoritism to obtain the profits generated by a well-run monopoly. Under this model, high-level corruption is not as serious a problem as low-level corruption under which officials “overfish” a “commons,” according to Olson, in their search for private gain. However, this claim ignores the fact that kleptocratic rulers have more power than lower level officials and may use this power to expand the resources under state control. Furthermore, even if they expand the state, kleptocrats frequently have a weak and disloyal civil service, a poor resource base, and a vague and confusing legal framework. Such kleptocrats, described as “official moguls” by Michael Johnston in Syndromes of Corruption: Wealth, Power, and Democracy (2005), favor a bloated and inefficient state that maximizes corrupt possibilities.

Table 4: Types Of Corrupt Government

Of course, some powerful rulers do manage to avoid inefficient policies. They enrich themselves and their families, but do not push rent-generating programs so far as to significantly undermine growth. Countries with a high degree of corruption that are politically secure and tightly controlled from the top may suffer from less inefficiency than those with an uncoordinated struggle for private gain. They have a long-run viewpoint and hence seek ways to constrain uncoordinated rent-seeking. This type of regime seems a rough approximation to some East Asian countries which have institutional mechanisms to cut back uncoordinated rent-seeking by both officials and private businesses. However, many corrupt rulers are not so secure. In fact, their very venality increases their insecurity. Furthermore, corruption at the top creates expectations among bureaucrats that they should share in the wealth and reduces the moral and psychological constraints on lower level officials.

Bilateral Monopolies And Mafia-Dominated States

The two cases where private interests exert power over the state differ depending upon whether or not the state is centrally organized to collect bribes. In the first, bilateral case, a corrupt ruler faces an organized oligarchy so that the rent extraction possibilities are shared between the oligarchs and the ruler. Their relative strength will determine the way gains are shared. Each side may seek to improve its own situation by making the other worse off through expropriating property, on the one hand, or engaging in violence, on the other.

In The Sicilian Mafia (1993), Diego Gambetta defines a mafia as an organized crime group that provides protective services that substitute for those provided by the state in ordinary societies. In some bilateral cases, the state and the mafia share the protection business and perhaps even have overlapping membership. Donatella della Porta and Alberto Vannucci, in Corrupt Exchanges: Actors, Resources, and Mechanisms of Political Corruption (1999), provide examples from Italy. Louise I. Shelley highlights this feature in a 2001 article, “Corruption and Organized Crime in Mexico in the Post-PRI Transition,” and Shelly and Svante E. Cornell, in a 2006 article, document state and mafia interpenetration in “The Drug Trade in Russia.”

A powerful corrupt ruler extorts a share of the mafias’ gains and has little interest in controlling criminal influence. If the mafias get the upper hand, they will enlist the state in limiting entry through threats of violence and the elimination of rivals. Furthermore, organized crime bosses who dominate business sectors may be more interested in quick profits through the export of a country’s assets and raw materials than in the difficult task of building up a modern industrial base. The end result is the delegitimation of government and the undermining of capitalist institutions.

Criminal mafias are only the most extreme form of private domination. Some states are economically dependent on the export of one or two primary products. These countries may establish long-term relationships with a few multinational firms. Both rulers and firms favor productive efficiency and the control of violent private groups, but the business and government alliance may permit firms and rulers to share the nation’s wealth at the expense of ordinary people. The division of gains will depend upon their relative bargaining power. If investors have the upper hand, there may not be much overt corruption, but the harm to ordinary citizens may, nevertheless, be severe. The size of the bribes is not the key variable. Instead, the economic distortions and the high costs of public projects measure the harm to citizens.

In the case when officials of a weak and disorganized state engage in freelance bribery but face concentrations of power in the private sector, the monopolist could be a domestic mafia, a single large corporation, or a close-knit oligarchy. Yet in each case, private power dominates the state, buying the cooperation of officials. The private actors are not powerful enough to take over the state and reorganize it into a unitary body, and the very disorganization of the state reduces the ability of the private group to purchase the benefits it wants. Making an agreement with one official will not discourage another from coming forward. Such a state is very dysfunctional as officials compete for corrupt handouts.

Competitive Bribery

In cases of competitive bribery, many low-level officials deal with large numbers of citizens and businesses. This could occur in a weak autocracy or in a democratic state with weak legal controls on corruption and poor public accountability. The competitive corruption case is not analogous to an efficient competitive market. A fundamental problem is the possibility of an upward spiral of corruption. The corruption of some encourages additional officials to accept bribes until all but the unreconstructed moralists are corrupt. Two equilibria are possible—one with pervasive corruption and another with very little corruption.

Reform requires systemic changes in expectations and in government behavior to move from a high corruption to a low corruption equilibrium. Unfortunately, the states that fall into this fourth category, such as many states in sub-Saharan Africa and in South and Southeast Asia, are precisely those that lack the centralized authority needed to carry out such reforms. The decentralized, competitive corrupt system is frequently well-entrenched, and no one has the power to administer the policy shock needed for reform.

Clientalism, Campaign Funds, And Private Wealth

More subtle and difficult pathologies arise in democracies with well-established competitive electoral systems. Democratic processes are expensive. Because the state can provide targeted benefits, award procurement contracts, and impose regulatory and tax costs, private interests seek political influence. Even if they only do this within the law, those with wealth are likely to do better than others. Of course, more diffuse interests have an impact both through the ballot box and through grassroots protests, but the well-off often can either co-opt mass opinion or counteract it through their own actions.

What can wealthy interests bring to the table beyond more pay for lobbyists and lawyers? In functioning democracies, a key resource is the provision of campaign funds and in-kind benefits, ranging from free media exposure to free travel and trips for volunteer campaign workers. Skirting close to the corrupt edge are the conflicts of interest that arise when government officials are given favorable access to investment opportunities, are promised private sector jobs, or are themselves associated with prominent business families. Even when there is no direct quid pro quo that runs afoul of anticorruption laws, ongoing connections and past patterns of favors can distort choices.

Clientalism operates in the other direction, as demonstrated in Junichi Kawata’s edited volume, Comparing Political Corruption and Clientalism (2006). Powerful politicians, sometimes in alliance with wealthy private interests, develop vertical ties that make ordinary citizens dependent on them for jobs; they also help with regulatory hurdles and access to public services. The state does not provide benefits to citizens as a right. Rather, its benefits are dispensed as favors, and costs are imposed on those who do not show proper deference. The clients may then provide help during electoral campaigns. Masaya Kobayashi, in the article “A Typology of Corrupt Networks” (2006), makes the useful distinction between the long-term reciprocal relations typical of clientalism and the specific purchase of services that characterizes bribery. Clientalism may be more deeply entrenched and harder to counteract than individual instances of corruption.

Restrictions on campaign finance are one response to both clientalism and corruption in established democracies. Solutions approach the problem from four dimensions. First, reducing the length of time for campaigns and limiting the methods available can reduce the costs of political campaigns. Second, stronger disclosure rules can be established. Disclosure permits citizens to vote against candidates who receive too much special interest money. In Voting with Dollars (2000), Bruce Ackerman and Ian Ayres, however, suggest the opposite strategy; they recommend that all donations should be anonymous so that no quid pro quo is possible. This idea invites donors to find ways to cheat, but if successful, it would likely discourage contributions from all but the most ideological donors.

Third, laws can limit both individual donations and candidates’ spending. In the United States, such limits are in tension with the constitutional protection of free speech. The basic issue, however, arises everywhere: To what extent can a democratic government interfere with citizens who wish to express their political interests through gifts to support political parties or individual candidates?

Fourth, alternative sources of funds can be found in the public sector. In the United States, the federal government provides funds for presidential candidates under certain conditions, and several American states provide public support for political campaigns. Also, a number of proposals have been made for more extensive public funding. One idea is to grant public funds to candidates who demonstrate substantial public support. Ackerman and Ayres, for example, argue that giving vouchers to voters to support the candidates of their choice could achieve this. This plan would combine public funding with an egalitarian system for allocating funds and, if combined with secrecy for private gifts, would reduce the influence of wealthy interests. If not well-monitored, however, it might increase illegal payments. Furthermore, their proposal does not respond to the pathologies of clientelistic systems where voters might still support entrenched incumbents who offer jobs and targeted services with little concern for broad public values.

Conclusions

All political systems fall short of the democratic ideal. Constitution writing and legislative drafting are pragmatic exercises requiring compromise and a realistic appreciation of the limits of institutions to control self-seeking behavior. Nevertheless, some political systems are worse than others. They have crossed the line into kleptocracy or into state capture—be it by mafias using intimidation and violence or by large business corporations leveraging their economic clout. Some states risk slipping into such pathologies and into outright failure, but one also needs to acknowledge the more subtle ways in which private wealth and public power can interact in more advanced systems. These interactions can undermine government legitimacy and divert the benefits of state action to narrow, unrepresentative groups. The policies required may not be as drastic and transformative as in kleptocratic or fully captured states, but they, nevertheless, require difficult confrontations with powerful vested interests both inside and outside of government.

Bibliography:

- Ackerman, Bruce, and Ian Ayres. Voting with Dollars. New Haven:Yale University Press, 2000.

- della Porta, Donatella, and Alberto Vannucci. Corrupt Exchanges: Actors, Resources, and Mechanisms of Political Corruption. New York: Aldine de Gruyter, 1999.

- Gambetta, Diego. The Sicilian Mafia. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1993.

- Jain, Arvind K., ed. The Political Economy of Corruption, London: Routledge, 2001.

- Johnston, Michael. Syndromes of Corruption:Wealth, Power, and Democracy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Kawata, Junichi, ed. Comparing Political Corruption and Clientalism. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2006.

- Khan, Mushtaq H., and K. S. Jomo, eds. Rents, Rent-Seeking, and Economic Development:Theory and Evidence in Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Kobayashi, Masaya. “A Typology of Corrupt Networks.” In Comparing Political Corruption and Clientalism, edited by Junichi Kawata, 1–23. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2006.

- Kunicová, Jana, and Susan Rose-Ackerman. “Electoral Rules and Constitutional Structures as Constraints on Corruption.” British Journal of Political Science 35, no. 4 (2005): 573–606.

- Olson, Mancur. “Dictatorship, Democracy, and Development.” American Political Science Review 87, no. 3 (1993): 567–575.

- Rose-Ackerman, Susan. Corruption: A Study in Political Economy, New York: Academic Press, 1978.

- Corruption and Government: Causes, Consequences, and Reform. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- International Handbook on the Economics of Corruption. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 2006.

- Rotberg, Robert I., ed. When States Fail: Causes and Consequences. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004.

- Shelley, Louise I. “Corruption and Organized Crime in Mexico in the Post-PRI Transition.” Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 17, no. 3 (2001): 213–231.

- Shelley, Louise I., and Svante E. Cornell. “The Drug Trade in Russia.” In Russian Business Power:The Role of Russian Business in Foreign and Security Relations, edited by Andeas Wenger, Jeronim Perovic´, and Robert W. Orttung. London: Routledge, 2006.

See also:

- How to Write a Political Science Essay

- Political Science Essay Topics

- Political Science Essay Examples