The South—sometimes refer red to as the global South— refers to the poorer countries in the international system, which are viewed also as lacking influence over the working of the international system and its institutions and are located in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

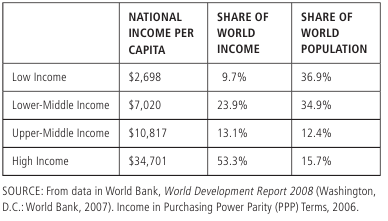

While this is not an homogenous group of countries, there is a relatively clear pattern of stratification in the international economic system that separates them from the rich countries of the North, as the following table indicates, using World Bank classifications.

Table 1

The first, low income, group is firmly within the South; the second and third are largely so (but include Russia and some of the poorer economies of eastern Europe). If we equate the “solid” South with the low and lower-middle groups, then it contains almost 72 percent of the world’s population but accounts for only 33.6 percent of world income.

The Third World In The International System

In the past, various terms have been used for this group of states. One which gained widespread currency was that of third world. This had the advantage of being a systemic concept, differentiating these countries from both the industrial societies of the capitalist first world and second world states that had adopted the state-socialist model. The logic of this term has been eroded with the disappearance of any coherent socialist bloc; however, its long history and analytic strengths lead many social scientists and political activists to continue to use the expression.

The third world effectively emerged as an international force in the post–World War II (1939–1945) era when a large number of colonial states achieved independence from European rule, joining the group of poorer states that had maintained their formal independence, such as those of Central and South America and China.

The process of decolonization took varied forms in different parts of the world, but in most cases was associated with a new, assertive nationalism that sought both to establish a unifying national political identity for the new states and to claim a significant place for them in the international order. The pioneering role in this process was played by India, which gained independence in 1947 under the leadership of a mass nationalist organization, the Indian National Congress, and a leader, Nehru, from its radical and internationalist wing. In some cases, the emerging national leaderships remained more closely tied to their former colonial masters. This introduced from an early stage a division in the third world between those states committed to assertive political and developmental policies and those prepared to accept a neocolonial status of continued subordination. The latter group often was shored up through external support from the former colonial powers in Africa and from the United States in Latin America.

By the mid-1950s radical nationalist currents had taken power in several third world states—in particular in India, Indonesia, and Egypt. An attempt was made to coordinate their role in the international political system under the banner of nonalignment. This doctrine sought to create a space, both domestic and international, between the cold war rivals capitalism and state-socialism. Nonaligned states refused to cast in their lots with either of these camps, claiming the right to adopt distinct positions in international affairs and to pursue national developmental policies that were socialist in some respects (for example, by undertaking land reform, expanding state ownership, and nationalizing some Western business operations) without embracing the full state-socialist model or excluding trade and investment ties with the capitalist states.

In April 1955, representatives of twenty-nine nonaligned governments met at the Asian-African Conference in Bandung, Indonesia, and in 1961, at the Belgrade Conference, the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) was born as a formal organization. The NAM has lacked sufficient coherence to be a major international force, but it continues in existence, with 118 members as of 2009. It provides a framework for coordination of views between third world states and was responsible for the launch of the proposal for a New International Economic Order in 1973. It also played an initiating role in the creation of the Group of 77 (formed in 1964– 1967), which seeks to coordinate third world positions in international economic negotiations. This structure—which as of 2008 has some 130 member states—overlaps closely with the NAM, but its focus on common economic interests has allowed it to become a more coherent force. The Group of 77 provides probably the best political definition of which states belong to the South or the third world in the international system.

The Third World In Social Science Theory

In the course of the 1950s and 1960s, two predominant paradigms emerged in the social sciences claiming to provide a social scientific understanding and policy prescriptions for the new third world states. One was modernization theory, the most influential approach in the academic mainstream of the North. The thrust of modernization theory was to assign the primary explanation for the backwardness of third world societies to internal forces. It saw the situation of the South as a result of their backwardness with respect to modern social structures that had developed in the North under the impetus of capitalism and industrialization. The challenge facing third world countries was to modernize their social institutions on the model of the developed countries and in its wake would follow economic development, rising income levels, and political democracy. Most modernization theorists felt that the postindependence elites had positive modernization agendas, although they were concerned that these were in danger of being derailed by hostile internal (and sometimes external) forces. A variant of this theory is the concept of political development, which accorded the political sphere some autonomy but applied the same modernization framework to it.

A contrary view was taken by the dependency school, which became increasingly influential from the 1960s onward. Linked with both Marxist academics and, especially in Latin America, with left-wing nationalist political forces, the dependency approach argued that the structural economic and social factors behind the poverty of third world countries had been created by the way they had been integrated into the international economy since the colonial period. The main source of third world poverty was not a failure to develop, but a particular form of development imposed by Western imperialism. In the memorable phrase of one of the pioneers of dependency theory, Andre Gunder Frank, what the third world suffered from was “the development of underdevelopment. ”The main cause of third world backwardness was thus external and the solution lay in breaking away from the externally oriented patterns imposed by imperialism and developing more autonomous, indigenous forms of economic activity.

The political conclusions of the dependency school were varied. On the one hand many of its advocates embraced a socialist model of third world development on Cuban or Chinese lines. Others, like the economists associated with the UN Economic Commission for Latin America, took a more reformist approach and promoted an import substitution industrialization (ISI) model of economic development that advocated shifting economic activities from primary producing export sectors to home-market based industrialization, with the support of tariff barriers.

Both modernization and dependency theories have been subject to extensive criticism. The modernization approach was seen as ignoring the historical specificity of third world societies and the international context of their development. Dependency theory suffered from the failure of the many attempts by third world countries to pursue ISI-based policies, and their almost universal conversion, under the pressure of international organizations such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, to a model of export-oriented growth and market liberalization. The ability of some third world economies, in the context of a shift in the international division of labor, to sustain significant industrial development, appeared to refute the original expectations of dependency theory.

However, dependency theory could claim to have captured more accurately the reality of third world societies: a distinct “underdeveloped” economic and social structure, characterized by a small, technologically modern industrial sector alongside a large agrarian and urban informal sector plagued by low levels of productivity and high levels of underemployment. These features look more like a distinct structural pattern, rather than a holdover from some “premodern” past, and this can explain why they have proved so intractable, despite decades of efforts to address underdevelopment.

The Domestic Politics Of Third World States

Much of the contemporary policy debates over the third world and its problems appear to be between descendants of either the modernization or dependency schools. For example, the views of the neoconservative architects of U.S. foreign policy seem firmly within the modernization tradition, while the perspectives of the new Latin American left owe much to the arguments of the dependency school.

The distinct social structure of underdevelopment has given the South correspondingly distinct patterns of domestic politics. The upper classes of the South have been relatively inchoate, growing out of deeply penetrated societies in which key economic sectors are under foreign ownership, and state and military institutions are heavily dependent on relations with external powers of the North. The key political elites often are based in the state apparatus—the military or the upper echelons of the state bureaucracy. The sort of national class-based political forms that coincided with the emergence of democratic institutions in the North have developed only episodically in the South. In their place two forms of political structures have tended to arise.

On the one hand, there is a form of politics in which power is tightly held by the state elites through military dictatorships or single-party states. Regimes of this type were common in the early postcolonial period, and often they were favored by the major Northern powers (both West and East), who saw them as reliable allies and a disciplined developmental force.

Such authoritarian regimes suffer from serious internal problems but often can hold power for long periods due to effective repression of opposition and the capacity to encapsulate elite aspirations within the regime, as the case of Indonesia illustrates. Inevitably, however, they encounter crises that they do not have the social resources to cope with and collapse under a combination of internal atrophy and social protest.

An alternative pattern is the development of broad, multiclass movements of a populist character built around charismatic leaders. Such movements often developed in the course of anticolonial and anti-imperialist struggles, but they also emerge in connection with the collapse of military regimes (especially in Latin America). While frequently espousing a vaguely socialist ideology, such regimes often are based on a set of alliances with traditional dominant groups and on a machine politics centered around patron-client relationships with their supporters.

This type of machine politics is inherently volatile and requires a lot of resources to keep the wheels oiled. Both military and populist regimes foster corruption, which generates political resources and rewards elite support for the regime. Populist regimes rarely overcome the limitations of the economies they govern and usually fail to meet the aspirations of their mass base. While they can become quite repressive in the face of serious opposition, they lack the repressive capacity of strictly military regimes and collapse more readily in the face of crises. It is therefore not unusual to see a pattern of military regimes alternating in power with populist forces.

A third tendency that has emerged as a powerful destabilizing force in third world politics is ethnically based nationalism, in which popular mobilizations take place around identities (often quite deliberately constructed by political forces) based on language and religion. Such mobilizations often center on access to state-allocated resources, but they also invoke powerful cultural and historical symbols that make intergroup relations difficult to negotiate and pave the way for brutal encounters. Any external shock to such precariously balanced political systems can enhance the competition for resources and spark intergroup conflict and the collapse of any form of effective governance. Both military and populist regimes have manipulated ethnically based tensions to reinforce their social base, and this often has been an important factor in starting the process of the ethnicization of politics.

Globalization And Structural Change In The South

Many of the economies of the South began to change significantly in the late 1970s as the economic structures of the North shifted. A combination of technological change and moves by large transnational firms to restructure their operations on a global level meant that the economies of the North shifted toward a postindustrial pattern centered in the service and technology sectors. This created a space for some economies in the South to expand their industrial sectors while remaining oriented toward international markets and produced a group of newly industrializing countries such as Brazil, Malaysia, Mexico, South Korea, and Taiwan. The differentiation of the South was further reinforced by the success of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, in forcing a major rise in international oil prices in the 1970s. This both enhanced the incomes of Southern oil exporters and produced new sources of capital that became available through the international financial system to finance development projects in the South.

This period, however, also saw a major rise in the international indebtedness of the South, as lending promoted by Northern financial institutions was directed often to poorly conceived “prestige” projects and distorted by political corruption. The international economic downturn of the 1980s further accentuated the lack of viability of many debt-funded schemes. This culminated in a new set of problems for the South, as high levels of debt service began to consume foreign exchange earnings and negate any benefits derived from international aid.

The most recent phase in the development of the South can be seen as an extension of this new international division of labor in the era of globalization. Two of the most populous states of the South—India and China—previously among the poorest countries in the world, have initiated a major new phase of industrial growth, achieving high and sustained growth rates over a period of several years. While they remain third world societies—plagued by unevenness of development and acute inequalities between urban and rural societies, between high and low technology sectors, and between upper and lower social classes—they are emerging as important players on the international economic scene, both at the state and the corporate level. This increase of economic power is gradually producing an increase in their political weight, but how rapidly this proceeds will depend on their ability to act in cooperation.

The Global South In International Politics

The states of the South have at various points in recent history attempted to act as a coherent bloc and influence both international affairs and economic relations. They hold a substantial majority in the General Assembly of the United Nations, and as a result that body has become a relatively autonomous force, although its influence is limited by the structure of the UN. India is making a bid to become a permanent member of the Security Council, a position already held by China, and if that were to happen the political weight of the South within the UN could be significantly strengthened.

The South has played an important role elsewhere in the UN system, using its leverage in the General Assembly to influence key appointments and to propel some UN agencies, such as the United Nations Committee on Trade and Development, to adopt critical stances with respect to the structure of the international system.

The unequal pattern—in terms of both political power and economic wealth—of North-South relations continues to be a key issue in international affairs. It also has moved from the realm of interstate relations to become an important concern in domestic politics around the world, expressed in forms such as the Make Poverty History campaign, the World Social Forum, and the formation of an influential aid lobby in many Northern states.

These concerns are given force by the data about the position of the South in the international economy. Despite more than four decades of official concern for international poverty and development, inequality in the international system appears to have worsened. Of particular concern is the situation of the very poorest countries in the international system—referred to by the World Bank as the least developed countries and sometimes as the fourth world. Corresponding to these difficulties are often acute domestic political problems that further undermine the capacity of their governments to address these issues or to make effective use of external assistance. In extreme cases, some of these countries collapse into failed states torn apart by civil strife. Afghanistan, the Congo, Liberia, and Rwanda are among the most prominent examples of this process.

One political force of global significance that has erupted from within the third world is that of radical Islamism. Its roots and dynamics are complex, but they can be seen as having a close connection with the poverty and political instabilities of the third world. Armed Islamism emerged in the 1980s out of the Afghan conflict, where the al-Qaeda network of Osama bin Laden was forged. Subsequently Bin Laden turned to sponsoring terrorist activities directed against the United States, culminating in the attack on the New York World Trade Center on September 11, 2001. As a consequence, Islamist terrorism became a key concern of American foreign policy and a major issue within the international system. Islam as a source of political identity and Islamism as a political program are firmly established within the Muslim world, in several countries as a popular political current within a democratic framework. Whether Islamist terrorism develops further will depend on many factors, in particular the ability of the international system to deal with issues of key symbolic significance to Muslims, such as Palestine (the one international problem on which there is a near consensus among third world states).

Another recent development in the South has been the emergence of radical left governments in several countries of Latin America. Drawing upon left-nationalist critiques of dependence, these new forces arise from political movements that appear to have deeper social roots than the radical populism of the past, although they continue to be marked by some of its traits. This development began in 1998 with the election of Hugo Chávez, a former military officer, as president of Venezuela. It was reinforced in 2003 with the election of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of the Workers Party as president of Brazil (although, in power, he has followed a cautious, reformist course).The subsequent election of radical presidents in Uruguay (2004), Bolivia (2005), and Ecuador (2006), along with the emergence of socialist and left-populist administrations in Chile, Uruguay, and Argentina, has produced a new left-wing axis in Latin American politics with a resonance throughout the South. It remains to be seen whether these regimes can sustain their initial objectives and contribute toward the political empowerment of the South.

The future of the South within the international order remains highly uncertain (compounded by yet new issues such as the impact of global climate change) but one thing seems sure—the issue of North-South relations and of global social justice will remain a central one both within international institutions and within the domestic politics of states both North and South.

Bibliography:

- Allen,Tim, and Alan Thomas, eds. Poverty and Development: Into the 21st Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Clapham, Christopher. Third World Politics: An Introduction. London: Routledge, 1990.

- Fieldhouse, David K. The West and the Third World. Oxford: Blackwell, 1999.

- Frank, Andre Gunder. Capitalism and Underdevelopment in Latin America. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1969. Group of 77, 2008, www.g77.org.

- Haynes, Jeff., ed. Democracy and Political Change in the Third World. London: Routledge, 2001.

- Third World Politics: A Concise Introduction. Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell, 1996.

- Hoogvelt, Anke. Globalisation and the Postcolonial World. Basingstoke, U.K.: Macmillan, 1997.

- Non-aligned Movement. N.d., www.cubanoal.cu/ingles/index.html. Roberts, J.Timmon, and Amy Bellone Hite, eds. The Globalization and Development Reader. Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell, 2007.

- United Nations Development Programme. The Human Development Report 2007–08. New York: UNDP, 2007.

- Also see reports for previous years. Volpi, Frédéric, and Francesco Cavatorta, eds. Democratization in the Muslim World: Changing Patterns of Authority and Power. London: Routledge, 2007.

- World Bank. World Development Report 2008.Washington, D.C.: World Bank, 2007. Also see reports for previous years.

This example South (Third World) Essay is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need a custom essay or research paper on this topic please use our writing services. EssayEmpire.com offers reliable custom essay writing services that can help you to receive high grades and impress your professors with the quality of each essay or research paper you hand in.

See also:

- How to Write a Political Science Essay

- Political Science Essay Topics

- Political Science Essay Examples