The welfare state was an essentially European invention that spread and developed in the states of western Europe and some of their New World offshoots. What is today known as the welfare state, Sozialstaat, l’état providence, or folkhemmet was most aptly described by historian Asa Briggs in a 1961 article as a state

in which organized power is deliberately used . . . in an effort to modify the play of market forces in at least three directions—first, by guaranteeing individuals and families a minimum income . . . ; second, by narrowing the extent of insecurity by enabling individuals and families to meet certain “social contingencies” (for example, sickness, old age and unemployment) . . . ; and third, by ensuring that all citizens . . . are offered the best standards available in relation to a certain agreed range of social services.” (228)

Origins Of The Welfare State

The Western concept of the welfare state emerged during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, when European societies were undergoing fundamental social, economic, and political changes—what historian Karl Polanyi called the “Great Transformation” in his groundbreaking 1944 book of the same title. Industrialization, the rise of capitalism, urbanization, and population growth had under mined the traditional forms of welfare provision offered by family networks, feudal ties, guilds, municipalities, and churches, creating a new class of disenfranchised poor. At the same time, the formation of nation-states, secularization of governance, and spread of mass democracy was creating an institutional framework for political articulation of social needs, and the gains in productivity resulting from industrialization provided the resources to meet them. This transformation was occurring in similar fashion throughout western Europe and parts of the New World, but the political responses to it, and the moral incentives for providing welfare and coping with what came to be known as die soziale Frage (the social question), varied widely.

There was remarkable diversity in the national trajectories of welfare state building and resultant social policy constellations. In the authoritarian European monarchies that pioneered social security legislation in the 1880s, social programs were imposed from the top down, while in the democracies of Switzerland and the New World, they emerged from the bottom up. Policy goals, types of institutions and financing mechanisms, program types and administration, the blends of public and private provision, and the use of cash transfers, social services, and regulatory policies all differ dramatically between nations. These multifarious manifestations of the welfare state are part of the varied legacy of state and nation building: of specific political contexts and cultures—particularly with respect to public trust, or lack thereof, in the state’s capacity to solve problems; of differing patterns of social cleavage based on class, ethnicity, or religion; and of different constellations of political and social actors and institutions.

When the first welfare states emerged in the nineteenth century, many social scientists, most notably the German economist Adolph Wagner in 1893, considered the phenomenon to be the direct fallout of industrialization and its accordant social and economic changes. According to Wagner’s Law, public expenditure in industrial economies was bound to consume ever larger portions of the gross national product, and this is exactly what happened over the course of the twentieth century. In the nineteenth century, the lion’s share of most national budgets went to military expenditures, and social programs just barely registered their presence. In 1890, for example, military expenditures in the industrialized countries comprised an average of 25 percent of total public expenditure, whereas social expenditures were only 4 percent. But by the beginning of the twenty-first century these warfare versus welfare spending priorities had been turned upside down. Among the countries of the developed world in the year 2000, the average spent on the military had shrunk to 4 percent, whereas that spent on social programs had increased to 40 percent of total public expenditure.

Wagner’s Law and the economic and social theories that built on it in the 1950s and 1960s were what social scientists call functionalist arguments in that they presumed social policy was driven exclusively by structural changes in the economy and society. According to such theories, welfare state expansion should have been a steady process that followed similar trajectories in all industrialized countries. In fact, however, expansion occurred in a sporadic manner, with spurts of growth and stagnation, while national welfare states came in a plethora of different sizes and shapes. In 2005, for example, U.S. public expenditure was only 15.9 percent of gross domestic product as compared to Sweden’s 29.4 percent. Modern theories of the welfare state account for these temporal and national idiosyncrasies by focusing on political determinants such as the partisan complexion of government, political institutions, and international influences. According to social scientist Walter Korpi’s Power Resources Theory, for example, the ways that labor parties and unions put their organizational capacities to use was a deciding factor in determining the trajectory of welfare state development. However, as historian Peter Baldwin (1990) has noted, no single configuration of socioeconomic variables or group of actors can fully explain the development of the welfare state. “Industrialization, free trade, capitalism, modernization, socialism, the working class, civil servants, corporatism, reformers, Catholicism, war—rare is the variable that has not been invoked to explain some aspect of [welfare state] development” (36–37).

In most countries, the welfare state’s first big growth spurt occurred between the two world wars. With the establishment of the International Labour Organization (ILO) in 1919, the first efforts to internationalize some aspects of social policy went into effect. The collapse of the central powers monarchies in World War I (1914–1918) and the subsequent democratization of Europe meant that huge new segments of society had a voice in government. Unions and parties representing laborers gained access to the corridors of power, and parties based on Christian social doctrines rose to the fore. In most countries, the Great Depression (1929–1939) put an end to this first phase of welfare state expansion, but in the United States and Scandinavia it actually provided an impetus to development. In the United States, where the postwar period saw relatively little welfare state development, the Great Depression unleashed the first major wave of expansion, what political scientists refer to as “welfare state takeoff.”

Post–World War II Development

World War II (1939–1945) and the subsequent drive to establish an internationally sanctioned world order to ensure peace and security had a major impact on welfare state development. European welfare states experienced their second massive growth spurt during the so-called trentes glorieuses, from 1945 to 1974.The ruling paradigm during this period was that increased economic integration and trade among European nations would forestall future conflicts, but European integration was a gradual process, and this second wave of welfare state expansion, which was episodic, took place in economies that were still relatively closed. Companies could not relocate beyond national borders to avoid taxation, nor was it easy for workers to migrate abroad in search of better wages. Solidarity was a requisite component of such economies, and governments of all partisan complexions took advantage of the opportunity to impose redistribution. The war had paved the way for public support of the Keynesian economic model, which had been developed during the depression. With whole societies in need of rebuilding, it was easy to justify high taxes and public expenditures if they promoted high employment and cared for the disabled and destitute. The idea that capitalist economies required government intrusion in economic and social affairs to manage demand and stabilize business cycles was widely accepted. Exceptionally high rates of postwar economic growth and a relatively even balance of power between labor unions and business interests tended to mitigate conflict over the distribution of wealth. The period has, in retrospect, been described as the “golden age” of welfare state development. Existing social programs were extended to cover new groups of beneficiaries, such as peasants or the self-employed, entirely new social welfare schemes were adopted, and there was a general increase in social benefits throughout the developed world.

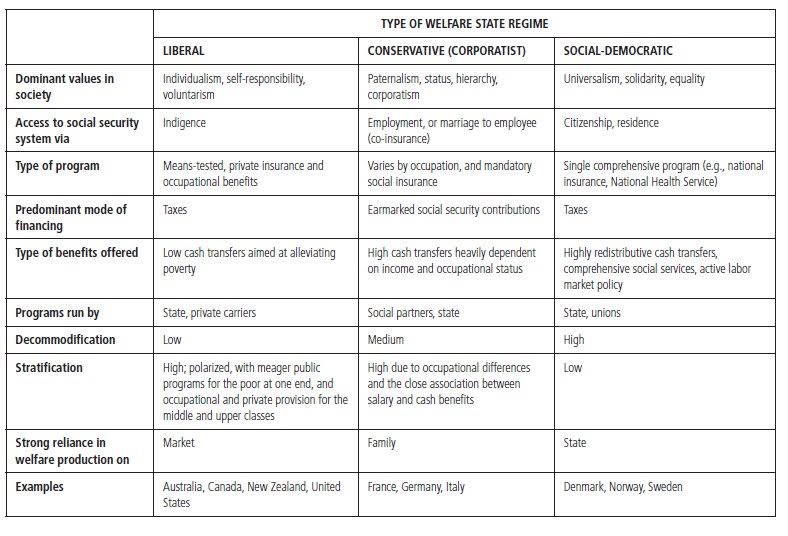

Even as nations became wealthier and welfare states expanded, the national differences in social expenditure levels and institutional patterns persisted and new ones developed. Various attempts have been made to classify the different types of welfare state, but sociologist Gøsta Esping-Andersen’s 1990 typology has proved the most useful. He defined three ideal types of welfare that encompass the full range of actual welfare states, what he calls three “worlds of welfare.” These worlds are distinguished by the impacts that a given social insurance arrangement has on decommodification: that is, the extent to which survival and well-being are independent of an individual’s labor market participation; its impact on stratification, meaning the amount of economic class division within a society; and who is responsible for welfare provision, whether the state, the market, or the family (see table 1). The distinctions between these three regimes, which are associated also with different systems of production and education, can be traced to the history of welfare state building, most notably to how effective the labor movement was at building cross-class coalitions (Korpi’s Power Resources Theory) and to the manner in which the Catholic Church’s social welfare system was or was not incorporated.

Critiques And Challenges

In the early 1980s, welfare capitalism began to falter and the golden age came to an end. The international political economy had undergone a fundamental transformation, beginning in the early 1970s with the collapse of the Bretton Woods financial system and the economic slowdown that the oilprice crises had triggered. Deteriorating economic performance and governments’ failure to cope with stagflation led to mounting public skepticism about the state’s role in social and economic affairs. The welfare state came under fire from all directions. Criticism came from across the political spectrum, but the biggest challenge came from proponents of neoliberalism and a new, morally engaged conservatism. They viewed high cash transfer rates as a distortion of the labor market that discouraged business investment and inhibited economic growth. From this perspective, the best way to deal with the new international economy was to “roll back the state” to its core functions. As neoliberal parties gained and wielded power in the 1980s, deregulation, the internationalization of capital markets, and escalating trade liberalization became the nor m. The 1990s were characterized by the emergence of a truly global economy that included the Single European Market and European Monetary Union.

In Europe the deepening of integration imposed constraints on fiscal and monetary policy that precluded Keynesian macroeconomic programs at the national level. It also meant that national welfare states lost a degree of sovereignty and became embedded in an emerging multilevel social policy regime. More generally, economic globalization created more competition between nation-states for footloose capital and investments, which depended in part on low labor costs and intensified pressures on national social standards. Enhanced exit options for capital made taxation and redistribution more difficult to implement and created an asymmetric balance of power between labor organizations and business interests.

Table 1: The Three Worlds Of Welfare Capitalism According To Gøsta Esping-Andersen

In addition to the external challenges posed by the emergence of the global economy, mature welfare states also have been confronted by a number of internal domestic challenges that are related to societal modernization and the transition from industrial to postindustrial economies. Service sector productivity is generally lower than industrial sector productivity. This means that the service sector generates lower rates of economic growth and smaller wage increases, both of which have negative feedback effects on public revenues. Private service sector jobs also tend to be less well-compensated than industrial jobs. Gains in employment in the private service sector can only be achieved by generating higher inequality, unless the public sector exercises a compensatory function. Some scholars have diagnosed these problems as the “trilemma of the service economy,” which they characterize as a tradeoff between employment growth, income equality, and sound state finances.

Competing in the global economy requires a flexible labor force that can be upsized, downsized, and transformed by retraining or replacements as demand changes and competitive advantages shift away from established industries. This need, as well as greater labor market participation by women, has led to the proliferation of part-time, temporary, and fixed-term jobs. The welfare state was not designed to accommodate these alternative forms of labor, which can be expected, in the long run, to produce large numbers of elderly poor. The increase in the number of women in the labor market also has decreased the capacity of families to provide welfare, as women who stayed at home were traditionally responsible for the care of children, elders, and the infirm. An increase in the numbers of single-parent households has had similar effects. At the same time, the erosion of traditional family forms and changes in male and female contributions have generated new social risks and needs, placing new demands on social care. Single parents and families with many children, for example, now comprise a significant percentage of the poor.

The two other potential challenges to national welfare states are demographic. Life expectancies have increased dramatically over the past decades, while fertility rates have declined. The result is an aging population and increased demand for the most expensive welfare state programs—pensions, health, and long-term care—that will require greater expenditures in the future. Scholars such as Alberto Alesina and Edward L. Glaeser also expect the increasing ethnic heterogeneity in European societies to pose problems for social-democratic and conservative welfare states. They maintain that these welfare states are based on a set of common values and political community, and that increasing ethnic heterogeneity will undermine this solidarity and make legitimation of redistribution impossible to achieve, pushing continental Europe toward American-style liberal social policy. Many scholars, however, disagree with this assessment.

Recent Reform Trends

National welfare state regimes have exhibited varying degrees of vulnerability and resistance to the problems and challenges that have plagued them since the 1980s, and they have followed quite different pathways to accommodate them. Nevertheless, there have been common trends in welfare state restructuring that stretch across the different types of regimes.

None of the established national welfare states were completely dismantled—popular support of the welfare state made it impossible to achieve legitimation for such measures—but retrenchment was common, with widespread reductions in benefits. Ironically, benefit cutbacks were outpaced by increasing expenditures due to rising unemployment, aging populations, and the emergence of new social risks. In almost all Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) nations since 1980, public and private social expenditures have increased. But while public social spending levels in the different types of welfare state regimes have converged over time, levels of private social expenditure have not. Furthermore, reductions in benefits have been asymmetrical, among programs within regimes, as well as among regimes, and in some areas benefits were increased or expanded. Since the mid-1990s, for example, most Western welfare states have attempted to increase employment rates and recognize the role of the family in welfare provision. There has been a general expansion of family policy, with a focus on paid parental leave programs, more social services for children, and the use of cash transfers and tax breaks for families with children.

With respect to old age pensions, there has been a general shift toward multipillar pension schemes. As attempts were made to decrease state liability for supporting aging populations, the reliance on private pension schemes increased. Most health reforms focused on cost containment. Here there was a curious tendency to cope with the inefficiencies of the established health care system by borrowing components from foreign systems: state-run health care systems introduced competition in the form of “quasi-markets,” social insurance systems encouraged competition between insurance carriers, and liberal health care regimes in the United States and Switzerland allowed for more state involvement. Labor market policies generally shifted away from passive support toward active and activation policies aimed at integrating the unemployed into the labor market, and at generally reducing welfare dependency. Worker training programs, wage subsidies, and job placement services for the unemployed have been greatly expanded. Typical coercive components of these policies include cutbacks in cash benefits, stricter conditions for benefit eligibility, shorter benefit duration for the able-bodied unemployed, and weaker employment protection and working time regulations.

These common trends in welfare state restructuring have led to some blurring of regime types, but the demarcation lines with respect to modes of financing, personal coverage, and benefit generosity persist much as they had during the postwar golden age. If we take into account the various private forms of provision and the impact of different tax systems, we see that major divides between contemporary welfare state regimes persist, determined not by their net amount of social spending, but rather, by differences in structure and institutional make-up. International comparisons of income distribution, poverty, and inequality make this readily apparent. While the distribution of market incomes has developed almost in parallel across OECD countries, the OECD showed for the early 2000s that inequality in disposable incomes was reduced by 40 percent in Sweden and only 5 percent in Korea—these were the two extremes. The impact of the particular mix of public and private benefit provision, for example, is readily apparent in a cross-national comparison. Poverty and inequality are significantly lower in Nordic and Bismarckian welfare states, where public provision is dominant, than in most liberal welfare states, where markets play a greater role. Indeed, Gøsta Esping-Andersen’s three worlds of welfare capitalism are clearly reflected in the OECD’s 2008 Gini-coeffcients of three representative countries: 0.38 for the United States, as the liberal welfare state; 0.30 for Germany, as the conservative one, and only 0.23 for social democratic Sweden.

Bibliography:

- Alber, Jens, and Neil Gilbert, eds. United in Diversity? Comparing Social Models in Europe and America. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Alesina, Alberto, and Edward L. Glaeser, eds. Fighting Poverty in the U.S. and Europe: A World of Difference. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Baldwin, Peter. The Politics of Social Solidarity: Class Bases of the European Welfare State, 1875–1975. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- Banting, Keith, and Will Kymlicka, eds. Multiculturalism and the Welfare State: Recognition and Redistribution in Contemporary Democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Briggs, Asa. “The Welfare State in Historical Perspective.” European Journal of Sociology 2 (1961): 221–258.

- Castles, Francis G., Stephan Leibfried, Jane Lewis, Herbert Obinger, and Chris Pierson, eds. The Oxford Handbook of the Welfare State. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Ebbinghaus, Bernhard, and Philip Manow, eds. Comparing Welfare Capitalism: Social Policy and Political Economy in Europe, Japan and the USA. London: Routledge, 2001.

- Esping-Andersen, Gøsta. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Cambridge, U.K.: Polity Press, 1990.

- Flora, Peter, and Jens Alber. “Modernization, Democratization, and the Development of Welfare States.” In Western Europe. The Development of Welfare States in Europe and America, edited by Peter Flora and Arnold J. Heidenheimer, 37–80. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction, 1981.

- Garrett, Geoffrey. Partisan Politics in a Global Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Hall, Peter A., and David Soskice, eds. Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Huber, Evelyne, and John D. Stephens. Development and Crisis of the Welfare State. Parties and Policies in Global Markets. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

- Iversen, Torben, and Thomas R. Cusack. “The Causes of Welfare State Expansion: Deindustrialization or Globalization?” World Politics 52 (2000): 313–349.

- Iversen, Torben, and John D. Stephens. “Partisan Politics, the Welfare State, and the Three Worlds of Human Capital Formation.” Comparative Political Studies 41 (2008): 600–637.

- Iversen, Torben, and Anne Wren. “Equality, Employment, and Budgetary Restraint: The Trilemma of the Service Economy.” World Politics 50, no. 4 (1998): 507–546.

- Leibfried, Stephan, and Steffen Mau, eds. Welfare States: Construction, Deconstruction, Reconstruction. 3 vols. Cheltenham, U.K.: Edward Elgar, 2008.

- Leibfried, Stephan, and Paul Pierson, eds. European Social Policy: Between Fragmentation and Integration. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, 1995.

- Lindert, Peter H. Growing Public: Social Spending end Economic Growth since the Eighteenth Century. 2 vols. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Obinger, Herbert, Stephan Leibfried, and Francis G. Castles, eds. Federalism and the Welfare State: New World and European Experiences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Growing Unequal? Income Distribution and Poverty in OECD Countries. Paris: OECD, 2008.

- Pierson, Paul, ed. The New Politics of the Welfare State. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Polanyi, Karl. The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time. Boston: Beacon, 1957.

- First published 1944 by Rinehart. Rimlinger, Gaston V. Welfare Policy and Industrialization in Europe, America, and Russia. New York: Wiley, 1971.

- Rothgang, Heinz, Mirella Cacace, Simone Grimmeisen, and Claus Wendt. The Changing Role of the State in OECD Health Care Systems: From Heterogeneity to Homogeneity? Basingstoke, U.K.: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

- Scharpf, Fritz W. “The Viability of Advanced Welfare States in the International Economy:Vulnerabilities and Options.” European Journal of Public Policy 7, no. 2 (2000): 190–228.

- Swank, Duane. Global Capital, Political Institutions, and Policy Change in Developed Welfare States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Wagner, Adolph. Grundlegung der politischen Ökonomie. Erster Theil. Grundlagen der Volkswirtschaft. Leipzig, Germany:Winter, 1893.

This example Welfare State Essay is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need a custom essay or research paper on this topic please use our writing services. EssayEmpire.com offers reliable custom essay writing services that can help you to receive high grades and impress your professors with the quality of each essay or research paper you hand in.

See also:

- How to Write a Political Science Essay

- Political Science Essay Topics

- Political Science Essay Examples